How Does Getting Hacked Actually Affect Company Value?

I think we may be about to see a major shift in Information Security—one which will come in the form of corporate business leaders—quite suddenly and dramatically—caring less about the prospect of being hacked.

Let me talk you through the idea.

The source of infosec budgets

I think most can agree that Information Security budgets are largely driven by fear. Decision makers within corporations still see being hacked as black magic. They don’t understand how it’s done, and they think the outcome is likely to be catastrophic if it happens to them.

And who can blame them? This is the narrative being pushed relentlessly through conferences like RSA, Blackhat, and others. As a result, business leaders are quite convinced that being hacked is a game changer—or even a game ender.

What would happen if they stopped believing that?

Worst case scenario

In order for the industry to be as cash-imbued as it is, it’s imperative that business leaders accept a key proposition:

Getting hacked will affect the value of your company.

This is the underlying fear of anyone who signs their names to multi-million dollar infosec budgets. And what’s the main metric for company value? Stock price.

So I got to wondering a while back how stock prices have actually been affected by hacks.

The numbers are scary, but not the way you’re thinking

I took a look at a few milestone hacks that have happened over the last several years, and the results were remarkable. The companies/incidents chosen were those involving Apple, Adobe, TJX, and EMC/RSA.

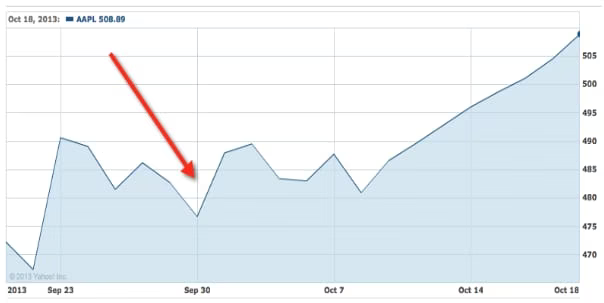

Apple

If you recall, Apple got compromised towards the end of July of this year (2013). Their Developer Network system got popped, and they lost some user information. It caused an outage of that part of the site for a number of days, and was a fairly big deal.

Check out the red arrow that points to when it happened, and notice what the stock does afterwards.

Hmm. A few blips, and then a sharp uptick. Where’s the fallout and backlash from the attack?

Ok, but the Apple wasn’t that big of a hack&mdash, and it was only some user details—not anything crucial like customer data. let’s look at something more significant.

Adobe

So let’s look at the Adobe hack that just happened a few days ago, in the beginning of October.

This was a major breach. We’re talking about 3 million customer credit card accounts, login data, and a ton of source code for their key products.

The result?

A slight dip for a few days. By October 15th they were back to business as usual. Evidently the public and investors have a short memory.

But again: this was a big breach, but not massive. Let’s look at a SERIOUS compromise.

TJX

I decided to go back and look at some more considerable breaches to get some context and make sure I wasn’t focusing on small fish that weren’t representative. So I took a look at one of the biggest breaches in history—the TJX compromise of 2007.

Huh?

First of all, we see a major increase in stock price here overall. That sucks for "sky is falling" charts

When we look for dips we find a couple of thems—but they don’t correspond to the time of the hack, which was in 2007!

Ok, fine, but their business isn’t technology or security. What about a company that’s identity and livelihood is based 100% on trust? Are there any examples of companies like that?

Yes.

EMC/RSA

The EMC (RSA) compromise is a great example because this company is responsible for trust and safety. Furthermore, the nature of the hack was a complete compromise of the very core of their business model, i.e. token information.

So, this type of compromise will clearly hit them hard and leave a mark, right?

Ok, this is just bizarre. They clearly took a hit at the time of the compromise, but based on all the other fluctuations it’s hard to even say conclusively that the hack was the reason.

More importantly, though, regardless of actual reason, it only took a few months to get back to their current price—after which time they then shot way above that price.

If you look at the stock from the beginning of 2011 to now, it looks like a pretty standard up and down fluctuation, with the OMG MASSIVE HACK OF DOOM not really doing much at all.

What this means

What we may have learned is that consumers and investors don’t care about companies being hacked. It flares up as a story for a short while and then goes back to business as usual. This lack of sustained impact seems to be caused by a few key points:

Desensitization: everyone is getting hacked, so it stops mattering when it happens

Apathy: people don’t have time to keep track of who’s insecure and who isn’t

Preferences: graphic designers who’ve been using Photoshop for 15 years aren’t switching to Painshop Pro because Adobe got hacked, and the same goes for other ingrained habits and inclinations

So that’s the consumer side. What about the security industry? I think it will change how infosec vendors sell themselves.

Less boogyman, more hard numbers

Once the fear of "compromise means close the doors" is no longer in play, company executives are going to need to see something traditionally compelling before spending money on security programs. Interesting idea—getting hard ROI numbers before a commitment of funding.

It puts information security in the same world as any other investment, i.e. needing to do more than wave the hands and show clips from The Matrix to get execs to spend money.

A future with less fear

So what does infosec look like in a world where the fear has been excorcised? I’ll give you a hint: It looks a lot more like accounting. Calculate the cost of x, y, and z, and don’t spend more than that to avoid those things. Again, it seems obvious, but emotion and logic are often mutually exclusive.

As for those in the industry, if you’re a vendor selling spiny whiz-bangs with synergistic marketecture—you might have some trouble up ahead. Individuals face similar challenges. If you’re in infosec because you heard it paid well, and you sell FUD for a living, you may want to start looking for the next big thing.

But if you’re a vendor that provides solid value, or a security professional that keeps a level head and can speak the language of the business, you’ll be just fine. This isn’t removing the need for information security; it’s simply bringing the conversation to the pitch and tone that it should have been in all along.

I for one will welcome the change. Information Security based on data rather than magic can only be positive. If only we could do the same with Security Theater in the physical realm.