Economic Inequality is the Norm, Not the Exception

May 24, 2018

I read and think a lot about technology, automation and how it will impact humanity.

One of the most important dynamics there is the potential for technology to increase income inequality, and for automation to take jobs from those who need them most.

For some reason—perhaps my being born and raised in the San Francisco Bay Area—I have mostly seen that change as new. I’ve been writing essay after essay warning that there was about to be a new and extreme separation between the top 5% rich and the bottom 80% poor.

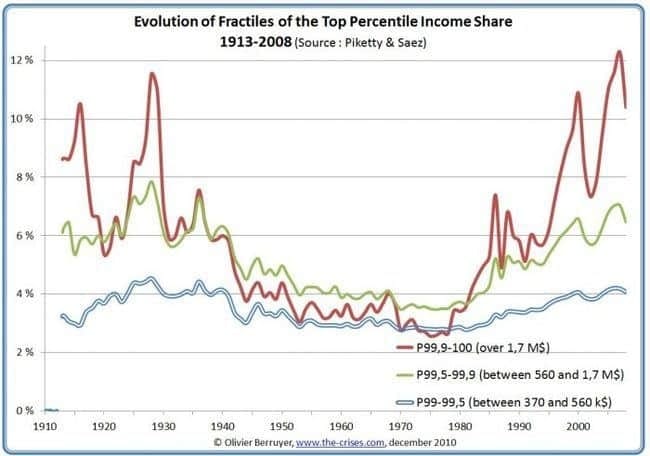

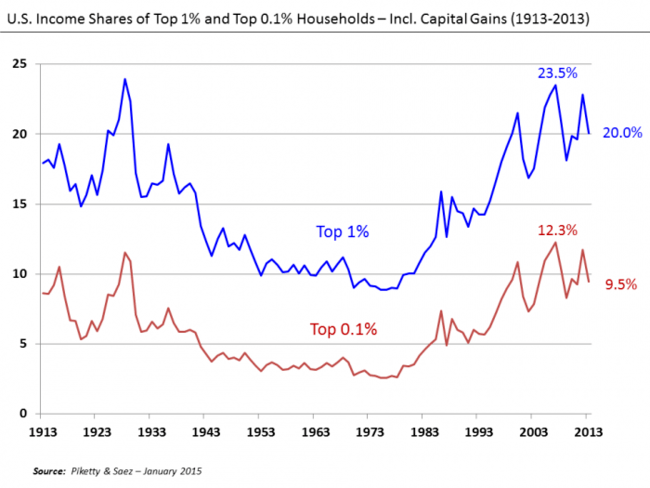

I still think that, but after reading books like Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century, and a couple dozen others, I’ve started to absorb his idea that inequality is normally high, and it’s only certain types of dramatic events that change that.

The big wars brought remarkable economic equality to the United States and Europe, for example, but inequality was high before then, and it’s returning to that state now.

But that’s just going a hundred years or so backward. What about looking back centuries or millennia?

I’m not a historian, but it seems to me that the difference between the rich and the poor has usually been quite vast. Let’s just take some civilizations that I can invoke from memory.

Sorry to anyone I’ve angered with this hurried list.

Ottomans

Egyptians

Mayans

Aztecs

Chinese

Greeks

Romans

Mongolians

Incas

Persians

Assyrians

Mesopotamians

Again, I’m not an expert on any of these civilizations, but based on a primary, secondary, and university education (and some basic searches just now) I can’t find any indicators that these were equal societies. They tended to have strong delineations between class, race, and religion that determined or influenced what your potential and ceiling was as an individual.

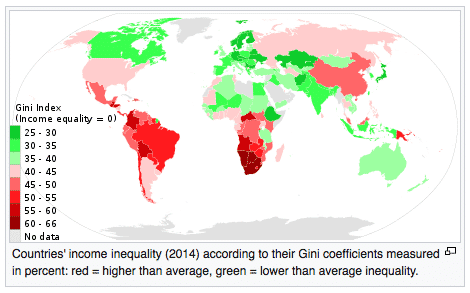

And we know this is the case for much of the last 500 years all over the world. There are the nobles, the merchants, the peasants, and the slaves. And in the "evolved" societies that transitioned to being the rich and the poor, with a shrinking middle/merchant, high-paid blue-collar class in the middle.

Anyway, the point here is not to say that inequality is ok because it’s always been that way. That’s silly. We also used to die of bad dental hygiene and used to think smells caused sickness, not the other way around. Progress is a good thing.

To oppose inequality we must oppose our human nature and human history.

I think we need to remember how new the idea of equality is as a concept. It was present in early Christianity as a concept of equality under God, was nurtured by the Stoics, and was introduced politically in the just the 1700s.

Until the eighteenth century, it was assumed that human beings are unequal by nature — i.e., that there was a natural human hierarchy. This postulate collapsed with the advent of the idea of natural right and its assumption of an equality of natural order among all human beings. ~ PLATO.STANFORD.EDU

It was then that thinkers started mixing the idea with government via Hobbes, Locke, Kant, Dahrendorf, Rousseau, Dworkin, and Vlastos. A major milestone in that journey was the French Revolution, where the people fundamentally rejected the idea that a small elite should have everything while everyone else had nothing.

Get a weekly breakdown of what's happening in security and tech—and why it matters.

The French Revolution

So we basically had a hundred years or so after the French Revolution and before the Industrial Revolution, where technology made it much easier for a few to make vast quantities of money. It also brought more material things to the masses, to be sure, but the fruits from those goods were not divided equally.

But then the wars happened, and as Piketty shows, major wars are an equalizer. To be more accurate, actually, catastrophes are equalizers.

Some call the economic unification of 1914-1945, The Great Compression.

Basically, when things are calm, the classes quickly separate into rich and poor. Then, if something happens to disrupt society—like a war, or a famine, or an epidemic—then the existing order is disrupted and things get mixed up again. Like a drink you have to regularly shake to keep homogenous.

Stratification in the fermenting process

The lesson for me was seeing that the default was the opposite of what I thought it was. Growing up I thought the default was equality and there must be an orchestrated evil at play to force the separation. But it seems that’s not the case.

Equality is not the default. It’s something we have to fight to enable.

The default state for humanity seems to be stratification, with the distance between top and bottom growing over time.

So with that as a given, we really need to find better ways to remix ourselves than disease, revolution, and war.