SEC vs. SolarWinds is Cybersecurity's ENRON Moment

The SEC’s case against Solarwinds > is transitioning cybersecurity from the world of wizardry to the world of accounting.

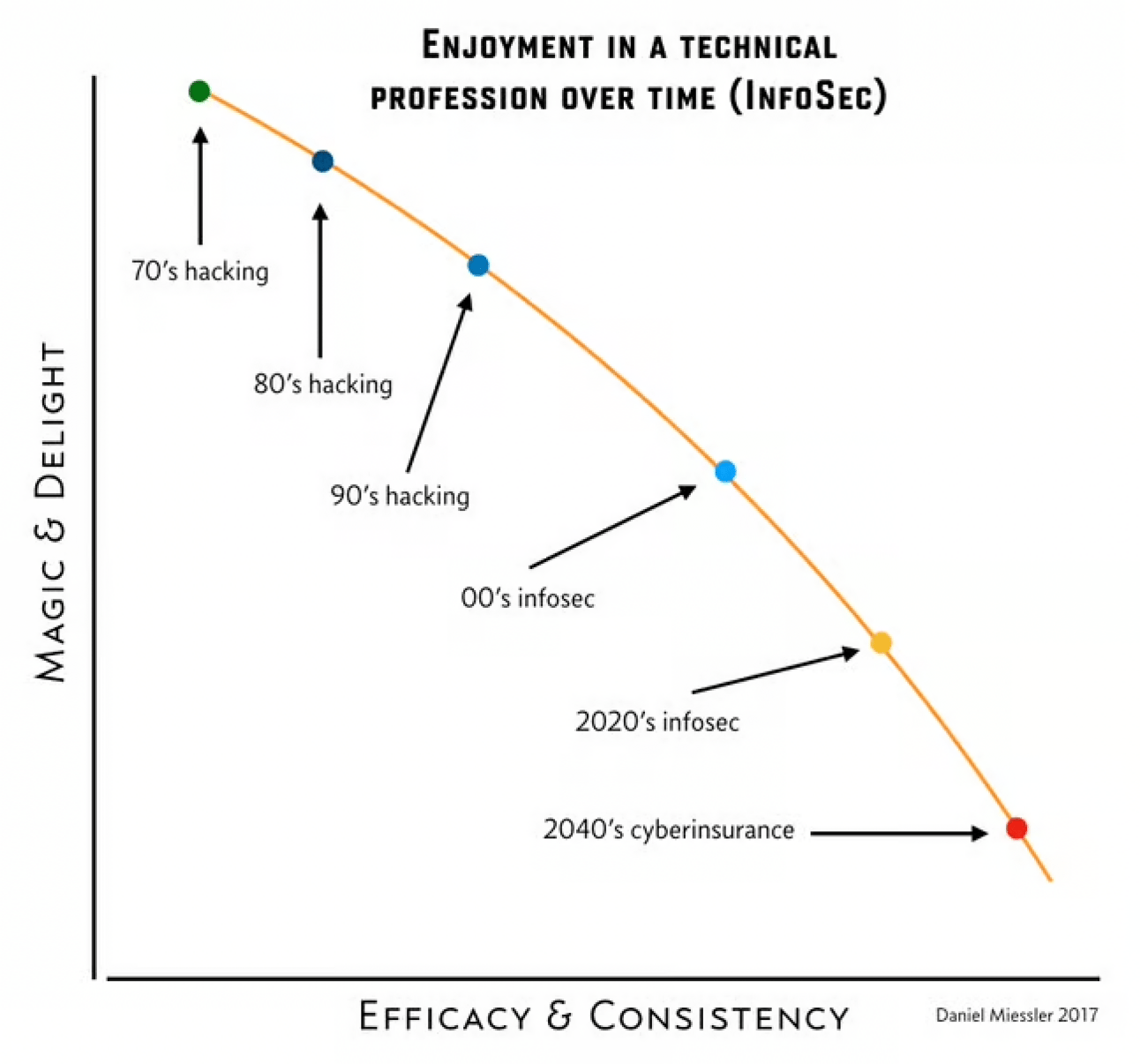

In my 2017 piece, Technical Professions Progress from Magical to Boring >, I talk about how this transition is inevitable for any new industry. You start without standards, and the only people who can do the arcane work are something like traveling magicians.

Then the industry grows up and processes start to take over. And within a few decades it’s more the process doing the work than the people.

My friend Saša Zdjelar > and I have been talking about this concept for over a decade. He used to work—and I used to consult—for a large oil/gas company that had the most advanced cybersecurity practices we’ve ever seen—even today.

They’re way over on the right side of the spectrum above—as close to accounting as possible. Approaching security this way is nowhere near as sexy, but we’ve seen numerous situations where companies throughout the industry get popped with something while this place stopped the attack at one of its layers. Every time it happens, we call each other and say something like:

Yet another thing we thought was over the top at the time, but turned out to just be ahead of the game.

The peculiar matter of risk ownership

As a quick diversion, one measure of this maturity is the question of who owns risk.

At advanced companies (at least in our view), the business / product owner always owns it, and it’s the job of specialists, such as infosec, to inform them of the facts. In other words, security can’t accept risk because they don’t own anything.

More organizations are catching onto this, but it’s surprisingly common to still have CISOs signing off on risk to business applications.

The SEC vs. SolarWinds situation

Anyway, the current case of SEC vs. Solarwinds is related but different.

In this scenario, we’re still talking about the transition from low-maturity to high-maturity, but we’re not specifically talking about who accepts the risk. In the case of Solarwinds, it wasn’t who accepted the risk, and it wasn’t a matter of being punished for getting hacked.

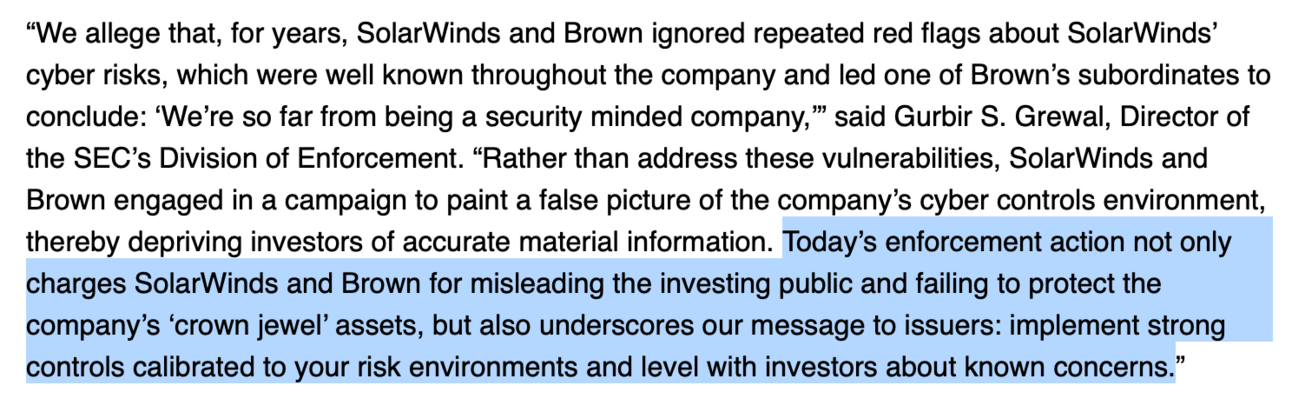

The SEC is bringing a case due to misrepresentation of the security state of the company. Quite simply (according to the complaint):

Many people in the company knew that the state of security and the security program were horrendous

At some point the CISO came to know this as well

But despite knowing this, the CISO continued to pass along and/or generate the claims that the security posture was healthy

I’m not saying those claims are true; I’m saying those are the claims being made.

>

>From the SEC Press Release

>So how is this an industry maturity issue?

To Saša and I, this case represents a clear maturity-defining moment because:

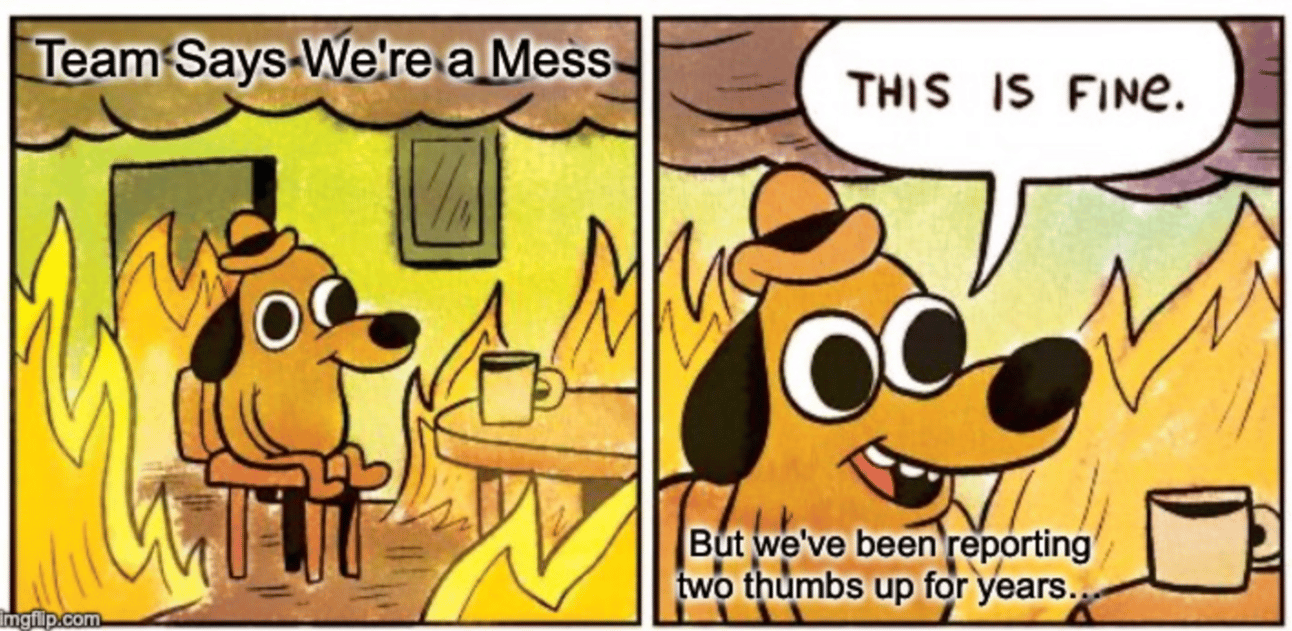

If Brown did in fact propagate such false claims, he would not be unique in that. In fact, having seen hundreds of companies throughout our career, we’d go so far as to say that this is very normal.

There is extraordinary pressure on newish CISOs to support the existing team’s findings, reports, and representations of the current security state. We’re not saying this is good. We’re saying it’s common.

In other words, in the old world, i.e., the current world, it’s very hard for a new CISO to come in and grab raw reports, see that things are a mess, start yelling at everyone, and then immediately and directly counteract the previous narrative to auditors and regulators that things are pretty ok.

There is extraordinary tradition and professional-courtesy-based inertia NOT to do this.

In the old (current) world, this would likely result in an immediate vote of no-confidence from their own security team, much of leadership, and from the business. It would be tremendously disruptive to the business and an indication that the CISO in question was not "adult enough" to sit at the big table.

We’ll change the narrative slowly and responsibly…you know—doing the right thing—but in a way that doesn’t destroy all the relationships and disrupt the business…

The well-meaning CISO passing along "this is fine" reportsVery few people do that. Instead, they hold their noses and pass along the reports to be a team player. And they try to right the ship from within now that they’re there.

To be clear, I’m not blaming them for this. Being a CISO right now is like standing on lava islands while juggling radioactive lightsabers. Tell the truth and you’re throwing the team under the bus and confessing you can’t do the job, and if you, um, "embellish", well, then you’re just lying.

The SEC throws a lifeline

As it turns out, this is precisely what the SEC is for.

Their job (or at least in this context) is to remove that inertia that’s practically forcing good, honest, hard-working CISOs to go with the flow and propagate reports that "this is fine".

❝It’s not that CISOs are trying to do the wrong thing; it’s that old-world inertia almost requires it of them.

So if my assumptions are correct—and I could very much be wrong because I don’t have all the facts—Solarwinds and Brown might be in the unfortunate position of being a transitory example case.

They could be right at the threshold of the old and new world of cybersecurity.

Anatomy of the new world

Ok, so we know what the old world is.

It’s where the CISO knows the program is a soup sandwich, and that we’re in a horrible state, but the last 5 reports have all said we’re in great shape. "Couple of minor issues", is what they said.

So now they have to choose between A:

Outing everyone who signed those previous reports

Calling massive scrutiny on the company

Ruining many personal and professional relationships which will affect their ability to be hired elsewhere

Throwing much of their current team under the bus

All this combined meaning they’re not likely to last long in the role

Or B:

Go with the flow to avoid all the above

Do the best they can to clean things up and shift the reporting to be more honest over time (while they remediate)

If you think you’d easily make the right choice given the above, I would say you’re either a saint or you haven’t played at the highest levels of this game.

This is especially true when new CISOs are supposed to show up and make things easier for the business, not harder. It’s political suicide to walk in, look at the reports, and pull the fire alarm.

❝This is a "doctor’s recommending certain brands of cigarettes" issue. It says less about the doctor and more about the time they lived in.

But that’s the old world. What will the new world look like if this SEC is successful?

Essentially, cyber will significantly move towards the seriousness of financial reporting, and the person accepting responsibility for cyber risk will be become a lot more like a CFO.

❝This is cybersecurity’s ENRON moment.

It’ll be like our ENRON moment—not in the sense of the offense committed—but in the sense of the reaction it spawns in regulators.

Saša and I think it’ll do one of two things:

Make the senior cybersecurity leader basically a Cyber-CFO, or

It’ll push the senior cybersecurity leader down into the VP or Director level, and the Cyber-CFO role will fall onto someone closer to the business, like a Chief Risk Officer.

In Scenario 2, this person would understand many different types of risk and be able to incorporate that knowledge into their deep understanding of the business.

So they’d be a business person first, then a risk expert. Not a risk expert first and then a business person.

❝It’s not enough to know the word "ROI" anymore—now security people are going to have to truly understand the business.

Saša ZdjelarOr, if it ends up being something more like Scenario 1, with existing CISOs becoming this person, they’ll have to be thinking a lot more like a CFO signing their name to financial reporting.

Meaning, if it’s wrong, that’s on them.

❝The top cybersecurity leader just became the Cyber "CFO". And if that’s not your thing, neither is being the top cybersecurity leader.

Saša ZdjelarThe analogy isn’t perfect, however, since cyber will still have a lot more subjectivity to risk ratings for the time being. But when it comes to "did we or did we not have X number of unpatched vulnerabilities", that’s going to be a lot more like adding up columns in Excel to notice that money is missing.

It changes the whole character of the role and its relationship to the board, auditors, and regulators.

The positive

The positive side of this change is that it’ll become a whole lot more common—and in fact expected—for a new CISO to blow the whistle when they see that the previous security leadership has been "fudging the reading".

That’s a good thing. And it’s my guess that this is precisely the effect the SEC is hoping to have in this case.

The negative for the security culture

The negative side of this is that security is still cool. Not as cool as it was in the 80’s or 90’s. But still cool.

This makes it less so.

In the minds of many people currently in security, this change will make the industry less hacking and more reporting. Less magic and more Excel. Less creativity and more audit trail. Less magic and more accounting.

But I think both can be true at the same time. It can be good for the industry overall while becoming more boring at the industry and senior leadership level.

Down in the weeds there are still spells that need casting.