My Response to Sam Harris vs. Very Bad Wizards II

The Very Bad Wizards just posted their follow-up episode to the first show (which I wrote about here) where they had Sam Harris on to talk about free will.

Part two was an interesting blend of fulfillment and frustration, as they seemed to simultaneously make progress while ending further apart than ever.

I have one central criticism: I think all three needed to re-summarize their positions more often in order to stay on point.

Entire 30 minute blocks were frequently lost on tangents of tangents without addressing the core disagreements, and this basically resulted in another stalemate.

So in the interest of my own sanity I am going to summarize and argue the main topics I think should have remained the centerpieces.

Emotional justification for blame

The primary argument being put forth by Tamler and Dave is that emotional response is a valid foundation for moral responsibility.

Tamler takes the emotional form of this, which is to say that someone is deserving of punishment if someone else thinks they are, and Dave’s major point here is to notice that accidental actions are different than intentional actions, and that this matters when determining how to punish or blame someone.

Fair enough.

And from a practical standpoint I think both Sam and I agree with this.

Where I disagree is on the point of whether it’s important to focus at all on the fact that people actually don’t have an option to do otherwise.

This crucial point was not sufficiently highlighted in the discussion, and I think I have a clear way add relief to this map.

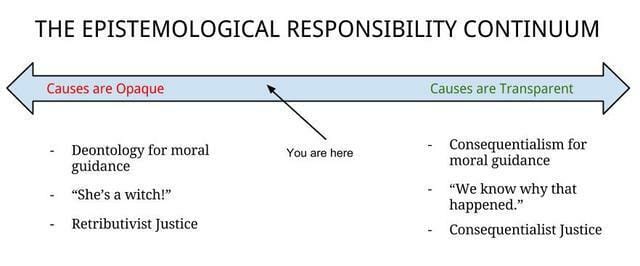

Imagine a continuum of human understanding (see the header image) of the world that moves from left to right advancing through time. So on the left we have the infancy of our species and complete confusion about cause and effect in the world. And on the right we are 10,000,000 years in the future where we can predict human behavior in high resolution.

The flaw with Tamler’s emotional basis for blame is that it doesn’t take into account how little any given victim understands the world.

One example that I used in my previous piece was a red-haired woman joining a farming village in 1239 right before a lightning storm kills a young boy.

The father of the boy—and the rest of the town—knows that the ginger girl brought the wrath of heaven down upon his only son, and he’s furious. So the townsfolk kill her the next day.

On Tamler’s view, she deserved punishment simply because the family was angry at her. But this was only so because they didn’t know how the world works with respect to causation.

And isn’t this precisely the situation we have today with determinism?

The family in the village didn’t understand weather, and the average human in 2015 doesn’t understand that our universe is mechanistic. As a result, a red-haired girl is burnt to a crisp in 1239 and drunk drivers are loathed in 2015.

Because the actual amount of control over undesirable outcomes is equally nonexistent for both the red-haired girl and the drunk driver—even for compatibilists—there is no way to differentiate how much blame they deserve that doesn’t involve asking the victim their thoughts on the matter.

Stated differently, Tamler and David are granting that nobody could have done otherwise, and that there are no varied degrees of this for voluntary or involuntary actions, yet they want to base moral responsibility on

Whether actions are voluntary

How people "feel" about the situation

Point #1 is simply false even on the compatibilist view, and point #2 brings us right back to stoning gingers or whatever other dumb shit people happen to believe in any given time period or culture.

What this means is that the resolution of any given blame framework correlates directly to that group’s understanding of how the world causally functions. If they’re on the left extreme they blame short people for floods and kill them on sight, and if they’re on the far right they don’t blame anyone for anything because they’re determinists.

In other words, the less you know about the world the more you 1) blame the person becasue they were the ulimate cause, and 2) the more you have a retributivist justice system. And the more you understand about the world the less you 1) blame the person becasue they were not the ultimate cause, and 2) the more consequentialist you become.

Get a weekly breakdown of what's happening in security and tech—and why it matters.

Tamler’s problem is he wants to sit on two different places on this continuum simultaneously. He wants to know that the person couldn’t do otherwise but still justify blame emotionally as if living in the middle ages.

He’s making a faulty assumption that regular folk are just like him…fully knowing people aren’t responsible, and then just indulging a temporary emotional response for the sake of sanity and integrity.

Real people aren’t like that. They’re ginger-killers who think drunk drivers deserve to be punished because they could have done otherwise. And they hold grudges—for years, decades, and lifetimes.

This is the moral framework that needs to die in a fire, and this is the reason it’s so important to accept and remember that determinism is not compatible with the commonsense notion of free will.

Once that’s sorted we can then talk about a practical approach to executing on a consequentialist criminal justice system—a system, by the way, that will likely look much the same if designed by either Tamler or myself.

But step one is moving towards the right on the spectrum above. We have to accept first that people are not ultimately responsible for their actions, and that any treatment as if they are should be based not on how the victim feels, but instead on what best helps all involved.

Emotional response should be seen much the same as cursing when you stub your toe. You’re allowed to curse passionately and creatively about it. For a moment…while the pain is heaviest upon you…while you can think of nothing else.

But after the pain subsides you have to go back to being well-behaved, and so it is with hatred and the desire for retribution. It’s not wrong to have these feelings. It’s wrong to think them justified after informed contemplation.

This is especially true if, like Tamler, you’re using the fact that you’re emotional as the justification for continuing to be emotional.

The deontology vs. compatibilism issue

This epistemelogical continuum shown above is also informative on the point of deontology vs. consequentialism.

During the episode Tamler accused Sam of being a closet Deontologist, and Sam said Tamler was smuggling consequentialism.

I think both positions are neatly unified by placing them on the same epistemlogical continuum discussed above. When you don’t know about the world, or about the effects that your actions might have as they ripple outward, then it’s best to use rules to guide your actions (deontology). And the more transparency you have into the world and its causes and effects, the more you’re talking about consequentialism.

They’re the same exact approach to morality: one is simply in a world with knowledge while the other is not.

Another way to say this is to say that deontologists are consequentialists living in a world before germ theory, and consequentialists are deontologists with a Tardis.

Summary

Tamler basing responsibility on emotional response turns the Holy Grail Witch Trial into a legitimate legal proceeding

The quality of a culture’s moral responsibility framework hinges upon its understanding of causation. As a result, we can reduce the prevalence of retributivist justice on Earth by teaching people early on that a mechanistic universe prohibits the ability for humans to do otherwise

Deontology and consequentialism are two ways of approaching the same moral truths: they’re simply optimized for different degrees of understanding of the world

Notes

I think Sam made points similar to these multiple times, but the conversation seemed bogged in the nuances of consequentialism

I highly recommended you subscribe to the Very Bad Wizards podcast if you haven’t already. Tamler and Dave approach topics with a delightful mixture of informality and sophistication that’s as addictive as it is endearing.

There is one aspect of Tamler’s position that I find extraordinarily courageous and respectable, which is the fundamental desire to have consistency and integrity in his intuitions and beliefs. He feels angry when something immoral happens, and he’s looking for a theory that this fits into, and I deeply respect that.

Dave frequently raises a question about why consequentialists should even care at all. Here’s my answer in deductive form: 1) Humans can experience happiness and suffering, 2) Humans agree that one is more or less desired than the other, 3) therefore we should pursue the one that is more desired. This is rooted in the deepest bedrock we have as sentient and conscious beings, i.e., our shared and subjective human experience. So to deny that we should try to increase happiness and reduce suffering essentially equates to rejecting a tautology such as "pain hurts", or "pleasure feels good".