My Analysis of the Disconnect Between Sam Harris and Jordan Peterson

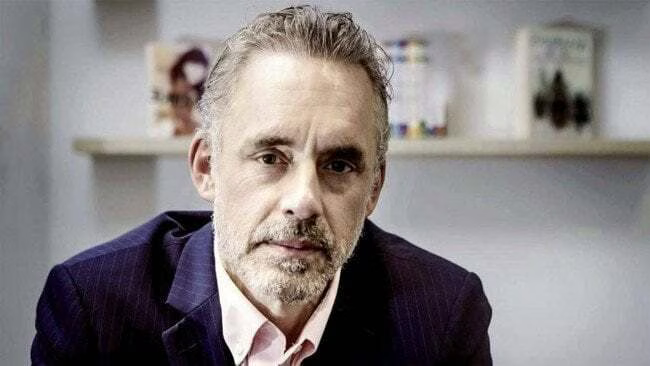

If you follow the work of either Jordan Peterson or Sam Harris you’ve no doubt seen them engage each other in various ways over the past year or so. Jordan has been on Sam’s podcast, which didn’t go well. They talk about each other to their respective audiences, and now they have a new video podcast series > together in Vancouver, moderated by Bret Weinstein.

I’ve been casually observing these interactions over the last year with some idea of where they’re missing each other, but haven’t felt the need to capture it until now. After watching the first Vancouver discussion I find myself compelled to engage. Their inability to clearly capture their differences has become a splinter in my brain.

What I’m going to attempt to do in this post is succinctly capture what each of them is saying, why they disagree with each other, and then what their audiences—and the world as a whole—actually needs to hear.

Sam Harris’ position

Sam sees harm in believing things that aren’t true, and much of his career is based on fighting those things. In Jordan he hears someone otherwise logical and intelligent (and kind and useful) say 7 good things out of ten, and then use the last three to go off into what basically equates to numerology. I’m not sure if he’s made that comparison, but I think he’d agree with it.

There could be some nuance here that’s not captured, but this is the basic idea of what he was saying.

In their first interaction, the big collision took place because Jordan refused to accept that facts were true on their own—instead insisting that things were only true if they were useful. This sent Sam into orbit, from which he seemed content to rain laser blasts upon Jordan’s head. Since I have known Sam longer, and therefore share more of his intuitions, I too saw this as a major flaw in Jordan, and I still do.

This same dynamic is at play with their new, more fundamental battleground of whether or not we should discard religion outright or whether there’s something useful there to preserve and make use of. Sam’s position is that:

Religion is clearly not true.

It’s often horrible.

Anything that is good and useful in it (which he admits there is some) can be found in other ways that don’t require belief in the supernatural.

For someone as smart as Jordan, with such a large audience, to say that he acts as if God exists, and to refuse to deny things like Jesus being reincarnated, he’s actually enabling and exalting very traditional and unsophisticated belief in religion—not the nuanced, usefulness-based scaffolding that Jordan seems to have constructed.

Jordan Petersons’ position

When I say tricks, I don’t mean that pejoratively. I mean that he is willing to use the various pecularities of the human mind to add valence to prescriptive guidance.

While Sam is first and foremost someone who protects objective truth from the irrational, Jordan is fundamentally someone who wants to help people, and he’s willing to use various tricks to accomplish that goal.

In this sense I actually give Jordan the upper hand here, as I see the practice of providing a prescriptive meaning infrastructure to be more direct and pure than Sam’s approach of helping people discard non-truth.

His entire career is based on finding patterns in stories, narratives, cultures, etc., which he then uses to construct a tangible plan to improve peoples’ lives. And he literally carries out this practice as his day job as a clinical psychologist.

So Jordan sees value in all these traditional stories and narratives, and he wants to use that value to help people. And he disagrees with Sam’s tendency and willingness to discard religions outright because of their downsides.

My analysis

My frustration in watching all this is that the disconnect seems obvious and avoidable. They’re obviously both correct. And they’re obviously both wrong.

Jordan is wrong to hide behind his custom-built, intellectually-nuanced, and utility-based belief system that he’s constructed because it’s obvious to Sam and his audience that to most people that Jordan just looks like a religious apologist.

To religious people who are looking for truth, Jordan is indistinguishable from a religious leader defending their faith.

That’s bad, because now we haven’t made the progress of getting them to decouple their understanding of reality from the belief in the supernatural—and all the negatives that come with that.

What should Jordan do about that? Simple. He should say something like this:

I am not a believer in the supernatural, or in any God, but I do believe that there are powerful forces within us humans, instilled by evolutionary biology, that work and can be controlled in large extent by the use of narrative, ritual, and story. What I have been doing is studying the patterns for these narratives and rituals for decades, and using that knowledge to help people improve their lives.

A possible Jordan Peterson

A possible Jordan PetersonThat to me would solve everything between he and Sam, since Sam has already said that he likes the infrastructure Jordan has built.

To be fair, Sam has mentioned elsewhere that he gets that pepole are asking for something, and that he recognizes that there’s a void there.

And Sam is wrong to downplay Jordan’s extraordinarily noble attempts to provide a semi-rational and culture-based belief system to millions who need it.

Here’s what I think Sam should say:

What Jordan is doing is fantastic. He’s used his knowledge of history, culture, and narrative to construct a meaning infrastructure that has ties to our past, our rituals, and many other elements that we’ve yet to understand out ourselves. My concern is simply that he’s not making it clear enough that he has built a secular system that is not tied at all to supernatural belief. And by not making that clear, while he uses religious language and symbology, it makes it look like he’s simply a new type of religious leader. That’s not helpful, as it keeps us tied to all the negatives that come with primitive religion.

A possible Sam Harris

A possible Sam HarrisThis is the type of argument that I think Jordan would respond to, and good conversation and change to his behavior would likely come from it.

Summary

Both men are progressives who are doing great work that’s helping many, many people. They’re simply coming at the problem from opposite directions.

Sam Harris’s fundamental drive is removing people’s harmful beliefs.

Jordan Peterson’s fundamental drive is providing positive belief.

This is why they are disagreeing: Sam doesn’t like Jordan sneaking in non-rational structure, and Jordan doesn’t want Sam to strip things away without replacing them with something else.

But humans don’t need another supernatural belief system—or more tacit support for existing bad ones—as that’s just punting from our existing set of horrible choices. But at the same time, humans are suffering right now, and stripping away their false beliefs doesn’t help them as much as the New Atheists probably hoped for. When you strip away, as modernity has done, you must also give something as an alternative, and that need is what Jordan has tapped into.

In short, Jordan should try to become more Sam-like in his clear delineation of the supernatural and the factual, and Sam should try to become more Jordan-like in his willingness to create a meaning infrastructure for those who need it.

Notes

This has been said other places, but I want to celebrate the dialogue that Sam has created, with Bret Weinstein’s help, that was evident in this series of discussions. It used to be that people would show up to watch people engage in dialectic, and I am overjoyed to see this as a possible form of entertainment (and enrichment) again. The fact that we can even have this type of dialogue, i.e., one in which people actually have good faith, mutual respect, and are willing to change their opinions at all, is spectacular on its own. So thank you to Sam, Bret, and all his guests that have been participating in this new type of discourse-based entertainment.

Another point that’s been made elsewhere, but Bret Weinstein added a dimension to the discussion that I’ve never seen before in a moderator. He was like a third participant, which is normally not allowed, but performing the moderator role. I think this might signal a pivot point in moderated discussions, assuming one can find people of Bret’s quality, where the third person is of the same caliber as the two participants but opts to serve the two rather than his own opinions. Bret was more than capable of being one of the two primary participants in this conversation, for example. But he chose to help them have a discussion. The positions could have been rotated, and the topic changed, and I think it would have gone equally as well. This should perhaps become a new paradigm for discussion, where the third person is not merely a referee, but rather a facilitator who is also an equal.