Framing is Everything

I'm starting to think Framing is everything.

Here are some of the framing dichotomies I'm noticing right now in the different groups of people I associate with and see interacting online.

AI and the future of work

FRAME 1: AI is just another example of big tech and big business and capitalism, which is all a scam designed to keep the rich and successful on top. And AI will make it even worse, screwing over all the regular people and giving all their money to the people who already have the most.

Takeaway: Why learn AI when it's all part of the evil machine of capitalism and greed?

FRAME 2: AI is just technology, and technology is inevitable. We don't choose technological revolutions; they just happen. And when they do, it's up to us to figure out how to adapt. That's often disruptive and difficult, but that's what technology is: disruption. The best way to proceed is with cautious optimism and energy, and to figure out how to make the best of it.

Takeaway: AI isn't good or evil; it's just inevitable technological change. Get out there and learn it!

America and race/gender

FRAME 1: America is founded on racism and sexism, is still extremely racist and sexist, and that means anyone successful in America is complicit. Anyone not succeeding in America (especially if they're a non-white male) can point to this as the reason. So it's kind of ok to just disconnect from the whole system of everything, because it's all poisoned and ruined.

Takeaway: Why try if the entire system is stacked against you?

FRAME 2: America started with a ton of racism and sexism, but that was mostly because the whole world was that way at the time. Since its founding, America has done more than any country to enable women and non-white people to thrive in business and politics. We know this is true because the numbers of non-white-male (or nondominant group) representation in business and politics vastly outnumber any other country or region in the world.

Takeaway: The US actually has the most diverse successful people on the planet. Get out there and hustle!

Success and failure

FRAME 1: The only people who can succeed in the west are those who have massive advantages, like rich parents, perfect upbringings, the best educations, etc. People like that are born lucky, and although they might work a lot they still don't really deserve what they have. Startup founders and other entrepreneurs like that are benefitting from tons of privilege and we need to stop looking up to them as examples.

Takeaway: Why try if it's all stacked against you?

FRAME 2: It's absolutely true that having a good upbringing is an advantage, i.e., parents who emphasized school and hard work and attainment as a goal growing up. But many of the people with that mentality are actually immigrants from other countries, like India and China. They didn't start rich; they hustled their way into success. They work their asses off, they save money, and they push their kids to be disciplined like them, which is why they end up so successful later in life.

Takeaway: The key is discipline and hustle. Everything else is secondary. Get out there!

Personal identity and trauma

FRAME 1: I'm special and the world out there is hostile to people like me. They don't see my value, and my strengths, and they don't acknowledge how I'm different. As a result of my differences, I've experienced so much trauma growing up, being constantly challenged by so-called normal people around me who were trying to make me like them. And that trauma is now the reason I'm unable to succeed like normal people.

Takeaway: Why won't people acknowledge my differences and my trauma? Why try if the world hates people like me?

FRAME 2: It's not about me. It's about what I can offer the world. There are people out there truly suffering, with no food to eat. I'm different than others, but that's not what matters. What matters is what I can offer. What I can give. What I can create. Being special is a superpower that I can use to change the world.

Takeaway: I've gone through some stuff, but it's not about me and my differences; it's about what I can do to improve the planet.

How much control we have in our lives

FRAME 1: Things are so much bigger than any of us. The world is evil and I can't help that. The rich are powerful and I can't help that. Some people are lucky and I'm not one of those people. Those are the people who get everything, and people like me get screwed. It's always been the case, and it always will.

Takeaway: There are only two kinds of people: the successful and the unsuccessful, and it's not up to us to decide which we are. And I'm clearly not one of the winners.

FRAME 2: There's no such thing as destiny. We make our own. When I fail, that's on me. I can shape my surroundings. I can change my conditions. I'm in control. It's up to me to put myself in the positions where I can get lucky. Discipline powers luck. I will succeed because I refuse not to.

Takeaway: If I'm not in the position I want to be in, that's on me to work harder until I am.

The practical power of different frames

Importantly, most frames aren't absolutely true or false.

Many frames can appear to contradict each other but be simultaneously true—or at least partially—depending on the situation or how you look at it.

FRAME 1 (Blame) This wasn't my fault. I got screwed by the flight being delayed!

FRAME 2 (Responsibility) This is still on me. I know delays happen a lot here, and I should have planned better and accounted for that.

Both of these are kind of true. Neither is actual reality. They're the ways we choose to interpret reality. There are infinite possible frames to choose from—not just an arbitrary two.

We all can—and do—choose between a thousand different versions of FRAME 1 (I'm screwed so why bother), and FRAME 2 (I choose to behave as if I'm empowered and disciplined) every day.

This is why you can have Chinedu, a 14-year-old kid from Lagos with the worst life in the world (parents killed, attacked by militias, lost friends in wartime, etc.), but he lights up any room he walks into with his smile. He's endlessly positive, and he goes on to start multiple businesses, a thriving family, and have a wonderful life.

Meanwhile, Brittany in Los Angeles grows up with most everything she could imagine, but she lives in social media and is constantly comparing her mansion to other people's mansions. She sees there are prettier girls out there. With more friends. And bigger houses. And so she's suicidal and on all sorts of medications.

This isn't a judgment of Brittany. At some level, her life is objectively worse than Chinedu's. Hook them up to some emotion-detecting-MRI or whatever and I'm sure you'll see more suffering in her brain, and more happiness in his. Objectively.

What I'm saying—and the point of this entire model—is that the quality of our respective lives might be more a matter of framing than of actual circumstance.

But this isn't just about extremes like Chinedu and Brittany. It applies to the entire spectrum between war-torn Myanmar and Atherton High. It applies to all of us.

The framing divergence

So here's where it gets interesting for society, and specifically for politics.

Our frames are massively diverging.

I think this—more than anything—explains how you can have such completely isolated pockets of people in a place like the SF Bay Area. Or in the US in general.

I have started to notice two distinct groups of people online and in person. There are many others, of course, but these two stand out.

GROUP 1: Listen to somewhat similar podcasts I do, have read over 20 non-fiction books in the last year, are relatively thin, are relatively active, they see the economy as booming, they're working in tech or starting a business, and they're 1000% bouncing with energy. They hardly watch much TV, if any, and hardly play any video games. If they have kids they're in a million different activities, sports, etc, and the conversation is all about where they'll go to college and what they'll likely do as a career. They see politics as horribly broken, are probably center-right, seem to be leaning more religious lately, and generally are optimistic about the future.

Energy and Outlook: Disciplined, driven, positive, and productive.

GROUP 2: They see the podcasts GROUP 1 listens to as a bunch of tech bros doing evil capitalist things. They're very unhealthy. Not active at all. Low energy. Constantly tired. They spend most of their time watching TV and playing video games. They think the US is racist and sexist and ruined. If they have kids they aren't doing many activities and are quite withdrawn, often with a focus on their personal issues and how those are causing trauma in their lives. Their view of politics is 100% focused on the extreme right and how evil they are, personified by Trump, and how the world is just going to hell.

Energy and Outlook: Undisciplined, moping, negative, and unproductive.

I see a million variations of these, and my friends and I are hybrids as well, but these seem like poles on some kind of spectrum.

But the thing that gets me is how different they are. And now imagine that for the entire country. But with far more frames and—therefore—subcultures.

They shape how you hear the news. They shape the media you consume. Which in turn shapes the lenses again.

This is so critical because they also determine who you hang out with, what you watch and listen to, and, therefore, how your perspectives are reinforced and updated. Repeat. ♻️

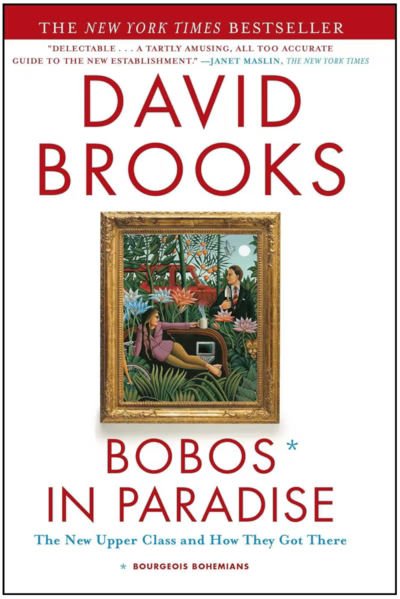

A couple of books

Two books that this makes me think of are Bobos in Paradise, by David Brooks, and Bowling Alone, by Robert Putnam.

They both highlight, in different ways, how groups are separating in the US, and how subgroups shoot off from what used to be the mainstream and become something else.

That's a key point in both books, actually: America used to largely be one group. The same cars. The same neighborhoods. The same washing machines. The same newspapers.

Most importantly, the same frames.

There were different religions and different preferences for things, but we largely interpreted reality the same way.

Here are some very rough examples of shared frames in—say—the 20th century in the United States:

- America is one of the best countries in the world

- I'm proud to be American

- You can get ahead if you work hard

- Equality isn't perfect, but it's improving

- I generally trust and respect my neighbors

- The future is bright

- Things are going to be ok

Those are huge frames to agree on. And if you look at those I've laid out above, you can see how different they are.

Ok, what does that mean for us?

I'm not sure what it means, other than divergence. Pockets. Subgroups. With vastly different perspectives and associated outcomes.

I imagine this will make it more difficult to find consensus in politics. ✅

I imagine it'll mean more internal strife. ✅

Less trust of our neighbors. More cynicism. ✅

And so on.

But to me, the most interesting thing about it is just understanding the dynamic and using that understanding to ask ourselves what we can do about it.

Summary

- Frames are lenses, not reality.

- Some lenses are more positive and productive than others.

- We can choose which frames to use, and those might shape our reality more than our actual circumstances.

- Changing frames can, therefore, change our outcomes.

- When it comes to social dynamics and politics, lenses determine our experienced reality.

- If we don't share lenses, we don't share reality.

- Maybe it's time to pick and champion some positive shared lenses.

Recommendations

Here are my early thoughts on recommendations, having just started exploring the model.

Identify your frames. They are like the voices you use to talk to yourself, and you should be very careful about those.

Look at the frames of the people around you. Talk to them and figure out what frames they're using. Think about the frames people have that you look up to vs. those you don't.

Consider changing your frames to better ones. Remember that frames aren't reality. They're useful or harmful ways of interpreting reality. Choose yours carefully.

When you disagree with someone, think about your respective understandings of reality. Adjust the conversation accordingly. Odds are you might think the same as them if you saw reality the way they do, and vice versa.

I'm going to continue thinking on this. I hope you do as well, and let me know what you come up with.

✉️ Email Me