An Encoding Primer

We’ve all been exposed to different types of character encoding while using the Internet. Some of these include ASCII >, ANSI >,Latin-1 >, ISO 8859-1 >, Unicode >, UTF-7 >, UTF-8 >, UCS-2 >, URL-encoding >, etc. There are a lot of them, and for many it’s very difficult to remember the differences between these standards, and when to use one vs. the other.

So let’s fix that. Permanently. Here, now, on one page.

Encoding > is simply the process oftransforming information from one format into another. It’s not magic, it’s not hard, andhaving a good understanding of the topic will help you a lot in the IT field. In this study > piece I’ll be covering both the underlying concepts as well as providing a quick reference for the most commonly used standards.

Concepts >

The best way to quickly grasp the basics of character encoding is to start with how ASCII > came to be.

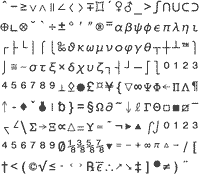

When UNIX and C were being developed there was only a need for unaccentedEnglish characters. As such, ASCII was created so that everything English (and theunprintable stuff like spaces and linefeeds >) could fit in 127 places, which tookup just 7 bits (0-127).

But since computers were using 8-bit bytes, various governments and groupsstarted thinking up of things to do with the other 128 places (128-255). The problemis that they didn’t agree on what to do with them, and chaos ensued. The result was thatdocuments sent from system to system often could not be read because they were usingdifferent character standards.

Finally, the IBM (OEM) and ANSI (Microsoft) systems were created, which defined code pages > that consisted of ASCII for the bottom 127 characters andthen a given language variation for the top 128 characters. So code pages 437 (IBM), 737 (Greek), 862 (Turkish), etc., were all 256 characters each, with ASCII as the first 127 and then their respective language for the other 128. This wayanyone using the same code page would be able to exchange documents without having hiscontent mangled.

This system of hotswapping code pages limped along until the Internet connected everyone and proved a) 8 bits aren’t enough, and b) exchanging text between systems all over the world is going to be the norm, not the exception. That lead to a fundamental shift in how encoding is accomplished. That brings us to the following:

It’s helpful to think of encoding methods as falling into two main categories–the old way and the new way.

The Old Way: Each character has a specific and direct representation on a computer.

The New Way: Each character is a concept, and can be represented in multiple ways.

The Old Way >

As mentioned, ASCII > is one of the first types ofencoding, and it uses the old way. In other words, ASCII characters are stored in a fixed number of bits in memory-all the time, every time. So an ASCII "D" always looks like this on a computer:

0100 0100

…which is 68 in decimal, and 44 in hex, etc. The problem with this approach is that it doesn’t scale. 8 bits only hold 256 combinations, and while English only has 26 characters in its alphabet (52 for capitals), you still need to add symbols, numbers, non-printable characters, etc. And that’s just English. Once you start adding all the other languages, many of which use accented and other special types of characters, 256 becomes a very low number.

The New Way >

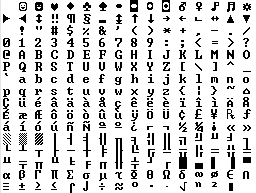

The newer, better solution is to not map characters directly at all, and to instead map them to a very specific conceptual entity which can then be described by a computer in multiple ways (using more bits/bytes as needed). This is what Unicode > does–it maps every letter of every language to a unique number (called a code point), so an upper-case "D" in Unicode maps to:

U+0044

This is always the case (sorry) regardless of the font used. One concept (letter) to one code point. So an upper-case "D" is always U+0044, and a lowercase "d" is not simply a "D" that looks different–it’s a completely different entity with its own number (U+0064). The numbers after the u+ are always in hex >. So now that you have set of individual numbers (code points) for characters you can decide how to handle them using a computer. This is the encoding part, which we’ll cover below in the standards section.

The key distinction between the old way and the new way is that the old way combined the characters themselves with how they were represented on a computer, whereas the new system decouples these pieces.

So in ASCII, for example, the letter "D" is always 7 bits, just like any other English letter, but in Unicode the letter "D" is just an idea that can be represented on a computer in a variety of ways.

This difference between the old and new systems is key to understanding character encoding. EBCDIC >, ASCII >, and code pages > are all examples of this old system of mapping directly to integers that are stored in a fixed way. Unicode > and the Universal Character Set > are examples of the new system that makes a distinction between identity and representation.

A Note About "Plain Text" >

Before proceeding we should address the concept of "plain text". "Plain Text" is a misnomer; it doesn’t actually exist. Talking about "plain" text with reference to a computer is like going into a supermarket and asking for "regular" food, or asking someone who speaks 200 languages to speak "normally". In short, the words regular, normal, and "plain" are all subjective, and computers don’t like subjective.

Email and Web Encoding Declarations (respectively)

The only way to describe how something is encoded to a computer is to tell it what standard to use. Period. Always explicitly define encoding in your documents; it will reduce by a significant margin the number of unexpected outcomes you experience.

The Standards >

Below I give some information on the common character encoding standards. I’ll do so in a repeating format that covers history, characteristics, and any references for the standard.

ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) >

History: ASCII > is one of the first computerized character systems in the world (after EBCDIC >). Initially an English-only and non-accented character system used back when the C programming language and UNIX operating systems were being created.

Characteristics: This is a 7-bit system (0-127). Characters from 0-31 are non-printable, and from 32-127 are the standard characters that people often mistakenly call "plain text".

Reference: The ASCII Standard (wikipedia.org) >, ASCII Table >.

Extended ASCII >

History: Extended ASCII is something of an informal name. It really just refers to how various groups handle the top 128 characters above the commonly accepted ASCII. So any system that’s compatible with ASCII for the first 0-127 characters, but has more above that, is considered "extended" ASCII.

Characteristics: Again, there isn’t really a strong definition of what "extended" ASCII is since it’s kind of a misnomer. Any character system that has content between 128 and 256 in addition to 0-127 is considered to be an implementation of extended ASCII. These include both code pages > and Unicode >.

Reference: Extended ASCII (wikipedia.org) >

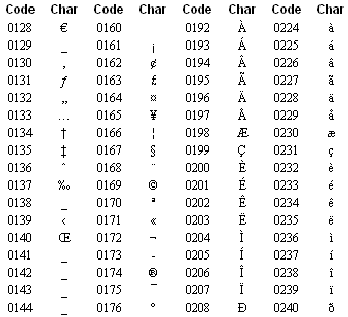

IBM Code Pages >

History: IBM Code Pages (also called OEM Code Pages) were created by IBM as a solution to everyone using the unused 8th bit in ASCII for their own purposes and causing confusion. They created a set of code mappings that included standard ASCII as the bottom 128 characters, but then various languages in the top 128, e.g. Greek >, Turkish >, Hebrew >, etc >. IBM code page 437 > is the original character set for the IBM PC.

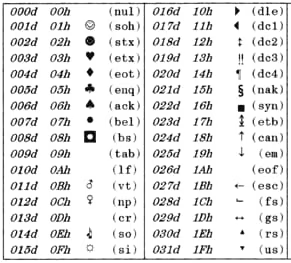

Characteristics: Code Pages contain the full 256 characters available from an 8-bit system, and include the agreed-upon ASCII at the bottom 127 (with some occasional variation) and then the top 128 vary based on the language, as indicated by the name. So the IBM code page 869 >, for example, is Greek in the top half and ASCII in the lower half–making a total of 256 characters.

Reference: IBM Code Page Reference (ibm.com) >

ANSI Code Pages >

History: The ANSI Code Pages are sets of characters very similar to IBM’s Code Pages, but were used in Microsoft operating systems. The name "ANSI" is interesting, as it implies that the mappings are standardized by ANSI, but they aren’t. The name came because ANSI Code Page 1252 > was supposedly based on a draft submitted to ANSI, but to this day ANSI has not made any of the "ANSI" standards official. So they’re best thought of as Microsoft standards.

Characteristics: ANSI Code Pages, like their IBM counterparts, contain the full 256 characters available from an 8-bit system, and include the agreed-upon ASCII at the bottom 127 (with some occasional variation) and then the top 128 vary based on the language, as indicated by the name. So the ANSI code page 1256 >, for example, is Arabic in the top half and ASCII in the lower half–making a total of 256 characters.

Reference: ANSI Code Pages > (wikipedia.org)

Unicode >

History: Unicode > is the result of a herculean effort to build a single code mapping (and encoding) system able to be used universally around the world. It was designed to replace code pages >, which are various language-specific character mappings of 256 characters each. The first version of Unicode was launched in 1988, created by representatives of Xerox and Apple.

Characteristics: As covered in the concepts > section (I recommend reading that first), it’s important to understand that Unicode separates character mapping from character encoding. On the mapping side, Unicode maps virtually every letter or symbol, in every language, to a unique code point, each of which is described by a U+ followed by four characters of hex >, e.g. the uppercase English letter "D" is represented by U+0044. Unicode defines 1,114,112 (220+216) individual code points in this way.

UTF-8/16/32 >

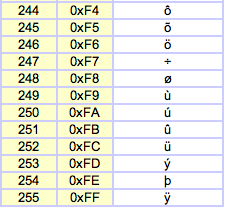

For the encoding side, Unicode has numerous ways of converting these code points into actual bits and bytes on a computer; these are called Unicode Transformation Formats > (UTFs). You’ve no doubt come across UTF-8 > in your travels, and that’s one option. But UTF-8 is not the only way you can encode a capital "D" (U+0044) in Unicode. Here’s a table that shows some alternatives:

unicode.org

The chart above reveals another misconception about Unicode: the "8" in "UTF-8" doesn’t indicate how many bits a code point gets encoded into. The final size of the encoded data is based on two things: a) the code unit size, and b) the number of code units used. So the 8 in UTF-8 stands for the code unit size, not the number of bits that will be used to encode a code point.

unicode.org

Image from: http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~mgk25/unicode.html

So now we see that UTF-8 can actually store a code point using between one and four bytes. I find it helpful to think of the code unit size as the "granularity level", or the "building block size" you have available to you. So with UTF-16 you can still only have four bytes maximum, but your code unit size is 16 bits, so your minimum number of bytes is two.

As an example of the various ways to encode the same content different ways, here is a chart that shows various ways you can encode English’s unaccented capital "D".

fileformat.info

UCS Encoding >

History: The Universal Character Set (UCS) is described in ISO/IEC Standard 10646 >, and was begun in 1989. Since 1991 the Unicode Consortium > has worked with ISO to develop The Unicode Standard and ISO/IEC 10646 in parallel. The character set, character names, and code points of Unicode exactly match UCS (with very few exceptions).

Characteristics: The UCS standard is basically a sister standard to Unicode >; they are extremely similar. The differences lie in the fact that UCS is an ISO standard while Unicode is backed by the Unicode Consortium, and Unicode supports a number of additional features beyond UCS, e.g. right-to-left language support.

Again, keep in mind that UCS/Unicode can be used interchangeably in many scenarios. Here is how their standards map to each other:

UCS to Unicode Mapping

UCS-2/4 >

UCS-2 > is an obsolete system that’s often confused with UTF-16. There is confusion because UCS-2 always used two (2) bytes per character, and the original concept for Unicode was two bytes per character as well, but that’s not the case now. UTF-16 has a minimum encoding of two bytes for any code point, but UTF-16 can use more than 2 bytes per character (up to four) because it supports surrogate pairs (pairs of 16-bit words).

In short, UCS-2 was a fixed-length encoding scheme with all code points encoding to two bytes, and UTF-16 is variable-length with two bytes as a minimum. But because they both had something to do with "two bytes" they often get confused. It’s a moot point anyway since UCS-2 is obsolete; if you need a 16 bit base, always use UTF-16.

UCS-4 > is identical, from a character mapping standpoint, to UTF-32 >. Both are fixed-length encoding schemes that encode every UCS/Unicode code point to 32 bits.

Reference: The Universal Character System (UCS) (ISO 10646) (wikipedia.org) >

UTF-7 >

History: SMTP specifies that data be transmitted in ASCII, and doesn’t allow bytes above the standard 0-127 range. The goal of UTF-7 was to make a system for encoding Unicode characters below 128 in a format that would pass through a classic SMTP implementation without being mangled.

Characteristics: UTF-7 is a 7-bit variable-length encoding system. It’s called UTF, but it’s not actually a Unicode standard itself. It encodes only the characters below 128 (it only has 7 bits to work with) by using one of two methods: For approximately 65 of the ASCII characters UTF-7 encodes them directly into the ASCII representation. For the rest it converts the character to UTF-16 and then performs Modified Base 64 Encoding > on them. From Wikipedia, the actual steps > are:

Express the UTF-16 characters in binary

Concatenate the binary sequences

Regroup the bits into groups of six

If the last group has less than six, add zeros

Replace each group of six bits with a Base64 code

Reference: UTF-7 (wikipedia.org) >

ISO 8859 >

History: ISO 8859 > is an early ISO standard (before UCS/Unicode) that attempted to unify code mapping systems.

Characteristics: ISO 8559 is an 8 bit system that groups various alphabets into parts >, which are then named 8859-1, 8859-2, etc. Here’s how they break down:

Part 1: Latin-1 | Western European

Part 2: Latin-2 | Central European

Part 3: Latin-3 | South European

Part 4: Latin-4 | North European

Part 5: Latin-Cyrillic

Part 6: Latin-Arabic

Part 7: Latin-Greek

Part 8: Latin-Hebrew

Part 9: Latin-5 | Turkish

Part 10: Latin-6 | Nordic

Part 11: Latin-Thai

Part 13: Latin-7 | Baltic Rim

Part 14: Latin-8 | Celtic

Part 15: Latin-9

Part 16: Latin-10 | South-Eastern European

This standard is pretty much obsoleted by UCS/Unicode. It’s like the standard that ISO wishes never happened. Avoid it when possible and use Unicode instead.

Reference: ISO 8859 (wikipedia.org) >

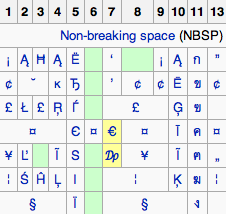

URL Encoding >

History: RFC 1738 (the standard for URLs) dictates that "Only alphanumerics [0-9a-zA-Z], the special characters– $-_.+!*'(), –and reserved characters used for their reserved purposes may be used unencoded within a URL." HTML allows any character in the ISO 8559-1 character set, and HTML 4 allows for anything in Unicode.

Characteristics: As a result of this requirement for URLs many common character sets cannot be used. All of ASCII can’t be used becauase much of it is unprintable. "Extended" ASCII (128-256) can’t be used because it’s not in the standard ASCII set. And some characters are simply a bad idea to use because it’s too easy to confuse them within URLs. Here’s a list of these from bloobery’s excellent page >:

Space

Quotes ""

Less Than "

Greater Than ">"

Pound "#"

Curley Braces {}

The Pipe Symbol |

The Backslash

The Carat ^

The Tilde ~

Brackets [ ]

The Command Tick `

For any of these characters listed that can’t (or shouldn’t be) be put in a URL natively, the following encoding algorithm must be used to make it properly URL-encoded:

Find the ISO 8859 >-1 code point for the character in question

Convert that code point to two characters of hex

Append a percent sign (%) to the front of the two hex characters

This is why you see so many instances of %20 in your URLs. That’s the URL-encoding for a space.

Reference: The W3C URL Encoding Reference >, URL Encoding (bloobery.com) >

FAQ >

Here I’ll try and address a number of common questions in question/answer format. If you have the time, however, I suggest you check out the concepts > and/or standards > sections first.

What’s the difference between Unicode and UCS (ISO 10646)? >

Think of Unicode and UCS as basically the same when it comes to character mapping. They almost mirror each other in this regard. Unicode, however, adds a number of features such as the ability to properly render right-to-left scripts, perform string sorting and comparison, etc. If ever in doubt you probably want to use Unicode.

What is the basic multilingual plane (BMP)? >

The BMP > is one of 17 sets of the total Unicode code space. It is the first one (plane 0), and has the most character assignments. Its purpose is to unify the character sets of all previous systems, and to support all writing systems currently being used.

I’m confused. Which schemes encode to which lengths? >

ASCII -> 7 bits

"Extended ASCII" -> 8 bits

UTF-7 -> 7 bits

IBM (OEM) Code Maps -> 8 bits

ANSI (Microsoft) Code Maps -> 8 bits

ISO 8859 -> 8 bits

UTF-8 -> 1-4 bytes

UTF-16 -> 2-4 bytes

UTF-32 -> 4 bytes

UCS-2 -> 2 bytes (obsolete)

UCS-4 -> 4 bytes

Conclusion >

I hope this has been helpful, and if you have any questions, comments, or corrections, please feel free to either comment below or contact me > directly. I’m also considering this my first draft, so if you have anything I should add to any of the sections to make it easier to understand, do let me know.