Why Dennett is Still Wrong About Free Will

I’ve argued against Dennett’s position on free will > multiple times in the past. I’ve always thought his argument was a bit squirmish. It was opaque, and it made one argument while appearing to all but a few to mean something else entirely.

In short, he was agreeing that the free will what both incompatibilists and regular people believe in doesn’t exist, and then trying to introduce another kind of free will that he said does matter.

The result was confusion.

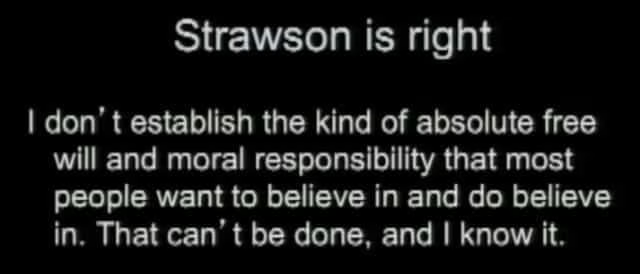

An extraordinary admission

And in his latest talk he makes good progress towards clarification. For starters, he comes right out and does three startling things:

Shows how many people agree that free will doesn’t exist

Gives strong scientific evidence that they’re right

Says very clearly that he agrees with them if they’re talking about the type of free will scientists or regular people are talking about

The admission that we don’t have the type of free will that 1) people think we have, or 2) that incompatibilists and most scientists think of as free will, is a major concession.

This is refreshing, and deserving of praise (!). But he’s obviously not giving up, so what’s his new angle? Let’s explore a few of the points he makes as he continues:

Involuntary vs. voluntary action

One of his weapons is highlighting the difference between voluntary and involuntary action. He has a line that goes like this:

There’s a difference between voluntary and involuntary actions

We know voluntary actions exist

Yet people are saying that free will is an illusion

You can’t have both free will as an illusion AND voluntary actions being different from involuntary ones

Therefore free will exists

As you know, with deductive arguments, if you accept all the premises then you must accept the conclusion. And if the conclusion is wrong then you must be able to find the error in on of them.

In this case, the error is in #4. It’s true that there’s a difference between voluntary and involuntary actions, but that doesn’t mean that free will exists. He’s basically trying to use voluntary action as evidence of free will, which is the entire thing he’s trying to prove.

Scott Adams comic

He then uses a Dilbert comic that talks about free will, presumably to bolster his position, not knowing that Scott Adams completely rejects free will. And he’s the one who came up with the term "moist robots".

Dennett goes on to say he likes that term, further illustrating how much he agrees with incompatibilists if their definition is used. Great, but what definition is he using, and most importantly, how is he justifying moral responsibility?

Absolute vs. Practical Free Will

One thing that I really liked, which I’m hesitant to take credit for, is he is now using the terms "Absolute" and "Practical" free will. This is a distinction that I have been trying to bring to the surface for years now, and I wonder if I could have possibly influenced his decision to use the terms.

He is essentially arguing, just as I do >, that 1) there is a distinction, and 2) the distinction is crucial to how we discuss the issue.

In short, Absolute Free will is the kind that I, Dennett, Harris, and most scientists reject. And Practical Free Will is the kind that I think most everyone would agree exists, if you define it as the useful experience of having choice.

The difference between Dennett and us, it appears, is simply whether the second kind (Practical) can get you to moral responsibility. I say no. Dennett says yes.

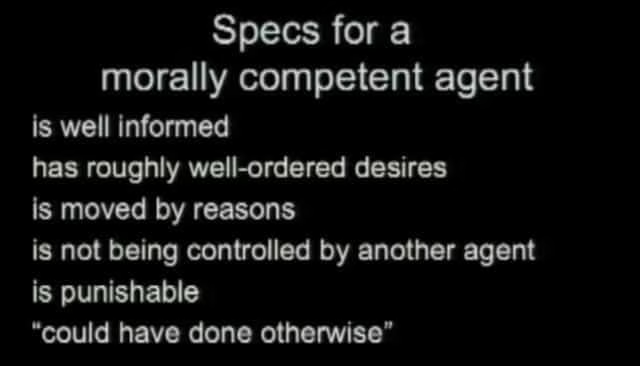

The requirements for moral responsibility

And this is where Dennett goes next, which is good because it’s the most important part. He starts by giving a list of things you must have to get moral responsibility, which are shown above.

First off, I’m not sure how he came up with the list. But let’s try to work with it. The meat seem to be in the last three:

Morally responsible people are not being controlled by others

Morally responsible people are punishable

Morally responsible people could have done otherwise

Causes are not control

He starts off on the first one by listing different types of "causes". One is a doctor giving good advice about heart health, another is a health fact on a Kellogg’s cereal leading to a good choice about heart health, another is a picture of a beautiful woman on a box of cereal asking you to buy the healthy cereal, and the last is a brain implant that compels you to buy the cereal.

He argues that these are all causes, but that being caused by an intervention is not the same as being controlled. This is curious coming from a determinist.

So now we have control of our actions sometimes, and not in others? If that’s the case then I think we probably disagree about the definition of determinism. As we’ll see more later, he is trying to eat his cake and sell it, too.

If you have determinism then all events are compelled—the question is simply one of awareness of some of these events, and assigning attribution to some of them as they pass through you.

Punishment is good because promises are good

This is an interesting one that I think betrays the underlying agenda he’s defending. He argues that incompatibilists are attacking punishment, or the morality of punishment, on the grounds that in a world without free will punishment would be wrong.

He says this is wrong because punishment is good.

I wouldn’t want to live in a world without punishment because I wouldn’t want to live in a world without promises. ~ Daniel Dennett

This is fascinating, and worth a discussion by itself. I wish we were having that conversation instead of this one.

I disagree with him, however, as I think that anyone who cares about promises will be sufficiently "punished" by the disappointment of letting someone down.

If the promise is to a close friend, the punishment is disappointment. If the promise is to society, the punishment is disappointment, or scorn, or ostracism. There are many options for repercussions that don’t have to bleed into retribution.

And he’s not come close to making a case that retribution can solve a problem that consequentialism cannot. This is especially true when a tinge of retributive salt could be added to a 99% consequentialist correction model. Consequentialism can absorb retributivist concepts, while the opposite seems impossible.

Could have done otherwise doesn’t violate determinism

He then goes on to address the most serious problem with determinism and moral responsibility: if someone could not have done otherwise then they can’t be held responsible for what they did do.

His answer is to give the putt example again, where people are arguing whether someone "could have" made a given putt that was missed. They argue back and forth saying that it definitely could have been made, but only if things were slightly different then the way they were.

So the compatibilist reading ends up being that if the golfer can make puts just like that one often enough, then we should be comfortable saying that he should have made that one as well.

Fascinating. Especially from a determinist.

So here’s what he’s asking us to conclude, brought into the real world: Anyone who could have made a better decision in life, like not pulling a trigger instead of pulling it, or saving the kid instead of being overcome by fear, can and should be punished for not having made that decision.

So, reducing that down, we can all be legitimately chastised because we did not do a better version of our previous actions? Any action. You got a Ph.D. Why didn’t you get two? You didn’t kill anyone in the prison camp, but why didn’t you save the other prisoners? You helped 20 people find a new home for their puppy. Why didn’t you save 100 puppies instead?

Remember, if you had 1,000 chances you probably could have done better in at least a few of them—and that’s what makes you guilty.

Abolish punishments in sports

He then goes on to argue that morality is a social construct, and that people are guilty of things simply because we’ve decided that anyone who does a particular thing is guilty.

That’s tidy.

He says Home runs are arbitrary, but agreed upon. So maybe a fly ball that goes 449 feet is an out, but a fly ball that goes 450 feet is a home run. And we’re ok with that because it’s about a social contract.

This is shell magic at its best. He’s completely taken our eyes off the question of who is hitting how far, and why.

If you go up to a hitter with a shoulder and hip injury, who just had stomach surgery, and tell him,

Hey buddy, the home run cutoff is 450 feet, and your family doesn’t get to eat if you don’t make it. But don’t worry if this doesn’t sound fair…it’s a social contract! We all agreed that 449 just isn’t enough to earn food.

That’s a brilliant foundation for morality. Especially when all those injuries were caused by a meteor that hit the guy’s house…while he was sleeping.

Oh, he should have had a meteor shield on his house? Because he was actually capable of having a meteor shield, in another universe where he had more tries at the defend-against-meteor putt?

Ridiculous.

Summary

Dennett made progress here and got my hopes up, but ultimately ended up in equally vacuous territory. He fails to adequately address the core problems with his argument:

If you’re a determinist like he is, it doesn’t matter how many variables are involved in the decision, because you don’t control any of them. He keeps trying to both accept that this type of free will doesn’t exist, while still trying to differentiate between a cereal box advertisement and a mind-control device. In a deterministic world they are ultimately the same.

Moral responsibility fundamentally reduces to the statement that, "You should have taken a different action than you did.", yet this is precisely what determinism says is impossible. The putt example is not an escape because all it does is ask us to question so-called "capabilities", i.e. it says that someone either could or could not have made a different choice. But this makes no sense given the fact that, given a deterministic universe, those capabilities are also outside the person’s control.

Dennett is committed to his position and I don’t think his mind can be changed regardless of how many putts we have him take.

Notes

I address the issue of "could have done otherwise" here in more detail >.