How to Build a Cybersecurity Career [ 2019 Update ]

I’ve been doing Information Security > (now called Cybersecurity by many) for around 20 years now, and I’ve spent most of that time writing about it as well. So I get a good amount of email asking the following question:

So this article is my answer to that question, with all the various aspects of the question presented in one place. It should give you the knowledge to go from complete novice, to getting your first job, to reaching the top of the industry.

Here’s how I have it broken down.

Let’s get started.

Education >

Information Security is an advanced discipline, meaning you should ideally be good at some other area of tech before entering it. This isn’t required, but it’s common and it’s ideal. The three areas that infosec people normally come from are:

System Administration

Networking

Development

Those are in order of most common entry points, not the best. Best would be development, then system administration, then networking.

But let’s assume you don’t have a background in any of those, and that you need to start from nothing. We need to learn you up, and there are three main ways of doing this:

University

Trade School

Certifications

I recommend doing a four-year program in Computer Science or Computer Information Systems or Information Technology with a decent university as the best option. But while you do it you need to be doing everything else in this article.

What you learn in college depends on the class content and your interaction with others, and the content you can likely get many different places. Hanging out and building stuff with a bunch of other smart people is the real benefit of university.

There are many who go to university for CS or Security and never become successful in the industry, and there are many who never go and reach the highest levels. University is not everything.

If you can’t do university you’ll need to learn another way, e.g., trade school or certifications. Any of these will do as long as you have the curiosity and self-discipline to complete what you start.

Here are the basic areas you need to get from either university, trade school, or self study/certification:

Networking (TCP/IP/switching/routing/protocols,etc.)

System Administration (Windows/Linux/Active Directory/hardening,etc.)

Programming (programming concepts/scripting/object orientation basics)

Database is in there as well, mixed in with system administration and programming.

If you don’t have a good foundation in all three of these, and ideally some decent strength in one of them, then it’s going to be hard for you to progress past the early stages of an information security career. The key at this point is to not have major holes in your game, and being weak in any of those is a major hole.

I’m going to talk more about certifications later, but I mention them above for one reason: you can use the certification study reading as teaching guides. They’re quite good at showing you the basics. Here are some examples:

A+

Security+

Linux+

CCNA

There are great reading out there (just Google for the best one) that can show you the basics of a topic quite rapidly. It’s a good way to make sure you don’t have any major gaps in your knowledge.

Programming

Programming is important enough to mention on its own. If you do not nurture your programming skills you will be severely limited in your information security career.

See the differences between programmer types here >.

You can get a job without being a programmer. You can even get a good job. And you can even get promoted to management. But you won’t ever hit the elite levels of infosec if you cannot build things. Websites. Tools. Proofs of concept. Etc.

If you can’t code, you’ll always be dependent on those who can.

Learn to code.

Input sources

One of the most important things for any infosec professional is a good set of inputs for news, articles, tools, etc.

This has traditionally been done with a list of preferred news sources based on the type of security the person is into. There are sites focused on network security, application security, OPSEC, OSINT, government security—whatever.

Increasingly, though, Twitter is replacing the following of websites. The primary reason for this is the freshness of data. Twitter is real-time, which gives it and advantage over traditional sources.

Twitter allows you to create (and subscribe to) lists. So if your username is @daniemiessler >, you can just append /list/listname to it and tweets from everyone in that list.

My recommendation is to use two main sources:

Twitter

RSS feeds

Follow people on Twitter who can expose you to new ways of thinking, new ways of learning things, and new knowledge for you to consume. And find all their sources and track those in your RSS reader. I recommend Feedly for RSS.

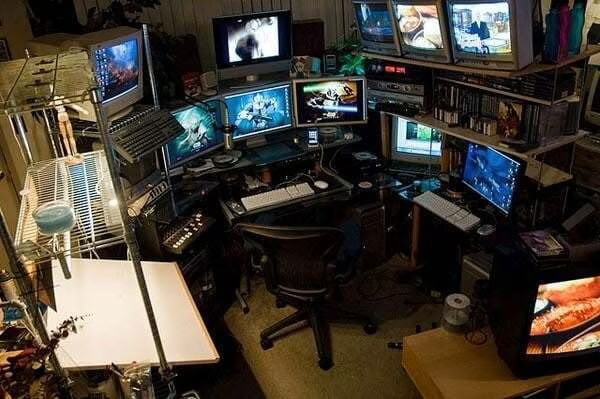

Building Your Lab >

Having a lab is essential. It’s actually one of the first things I ask when I’m looking at candidates during interviews. I ask what kind of lab or network they have to play with, and if they reply that they don’t have either I thank them for their time.

The lab is where you learn. The lab is where you run your projects. The lab is where you grow.

There are a few options for lab setups.

VMware (or similar) on a laptop or desktop

VMware (or similar) on a laptop or desktop that’s now a server

A real server with VMware (or similar) on it

VPS systems online (EC2, Linode, Digital Ocean, LightSail, etc.)

I recommend a combination of #3 and #4 if you have the money, with #3 coming first. Here are some of the things you want to be able to do in such a lab:

Build an Active Directory forest for your house

Run your own DNS from Active Directory

Run your own DHCP server from Active Directory

Have multiple zones in your network, including a DMZ if you’re going to serve services out of the house

Graduate up to a real firewall as soon as possible. I recommend Sophos’ firewall (previously Astaro), as I’ve been using it since it came out, but there are other good iptables and pf options. Doing this will require you to learn about routing and NAT and all sorts of basics that are truly essential for progression.

Stand up a website on Windows/IIS

Stand up a website on Linux/PHP

Build a blog on Linux/Wordpress

Have a Kali Linux installation always ready to go

Build an OpenBSD box and create a DNS Server using DJBDNS

Set up a proxy server

Build and run your own VPN on a VPS

Build and configure an email server that can send email to the Internet using Postfix, Qmail, or Sendmail (I recommend Postfix)

I used a number of terms above that you may need to look up. Take that as an exercise!

These are the basics. Most people who are hardcore into infosec have done the list above dozens or hundreds of times over the years.

The advantage of a lab is that you now have a place to experiment. You hear about something from your news intake, and you can hop onto your lab, spin up a box, and muck about with it. That’s invaluable for a growing infosec mind.

Now that you have that list going, you can start focusing on your own projects.

You Are Your Projects >

This is where the book knowledge stops and creativity begins. You should always be working on projects.

As a beginner, or even as an advanced practitioner, nobody should ever ask you what you’re working on and you say, "Nothing." Unless you’re taking a break in-between, of course.

Projects tend to cross significantly into programming. The idea is that you come up with a tool or utility that might be useful to people, and you go and make it.

And while you’re learning, don’t worry too much if someone has already done something beforehand. It’s fun to create, and you want to get used to the thrill of going from concept to completion using code.

The key skill you’re trying to nurture is the ability to identify a problem with the way things are currently done, and then to 1) come up with a solution, and 2) create the tool to solve it.

Projects show that you can actually apply knowledge, as opposed to just collecting it.

Don’t think about how many projects you have. If you approach it that way it’ll be artificial. Instead, just focus on interesting problems in security, and let the ideas and projects come to you naturally.

In the writing world, there’s a maximum that says, "Show, don’t tell". Projects are showing, and collecting knowledge is telling.

Practicing with Bounties >

Now that you have a lab, have some solid skills, and some projects you’ve been hacking on, you may want to work on some bug bounties.

The reason for this is best summarized as a fast track to real experience, which is the #1 ask of anyone looking to give you a job. So in addition to coding experience (with your projects), with bounties you can also gain testing experience.

There are two main platforms you can do bounties on: BugCrowd, and HackerOne. There are many more but those have the most programs and the most maturity.

The process is that you register on the site, look for a program you’re interested in looking for bugs on, and then you jump right in. Here are a few things to keep in mind:

Read the rules and limitations associated with each program very carefully. You don’t want to run afoul of either the platform or the customer.

There are multiple types of bounty program. Some pay money and are higher scrutiny and competition, and others are more for Karma, or Kudos, and are better opportunities for beginners to practice.

I highly recommend Jason Haddix’s content for web bounties; learning his methodology is the fastest way to start finding bugs.

The world is quite nuanced, with a number of rules and a unique etiquette that you should learn. So be respectful of that and you’ll be more efficient and less likely to step on toes.

For both programming on GitHub and doing bounties, the goal is to gain professional experience before you get a job, or before you get a job in the field you want. It’s the way to show rather than tell.

Having an active GitHub and having some solid bug finds in your bounty profiles is a way to set yourself far apart from someone who is still pure theory, and can easily help you get your first position, or a new position in a field you’re not yet established in.

Have a Presence >

Ok, now that you’ve done a few projects it’s time to let people know about them through your brand platform. Yes, you should have a brand. It can be low-key if you wish, and the industry is already full of too many egos, but you do need a platform to broadcast from.

If you’re an introvert and/or you feel like it’s boastful to talk about anything you’ve done, stop it. This is not an industry where that mentality will help you. To get to the mid to high tiers you need to learn how to market yourself and your work.

Introversion and (false?)humility will not do. Do good work and be willing to talk about it. But do so from a sharing and collaboration angle, not from a position of arrogance.

Website

First you need a website. Some call this a blog, and that’s fine. The point is that you need a place to present yourself from. You should have an about page, some good contact information, a list of your projects, etc. And again, if you blog then that’s the place to do it.

Just understand that Your domain and your website are the center of your identity, so ideally you’d have a good domain that will last a literal lifetime. firstnamelastname.com is probably ideal, but many people cannot do that because their names are fairly common. There are other options, but choose carefully. You want this domain to remain the same until you die, or get taken into the rapture, or get uploaded into the collective.

Pick something good is what I’m saying. It’s your brand, and your brand matters.

You should blog and host all your projects on your own site and syndicate everywhere else.

Avoid writing too much on other services like Medium or Blogger—and definitely avoid Facebook for anything but random thoughts or interactions. If you create anything interesting on platforms that aren’t your own domain, turn it into a complete piece and bring it home to your own site.

Same with Twitter. Have a good handle. Ideally firstnamelastname, but if you can’t do that pick a good alternative. Again, this is permanent personal infrastructure, so don’t make it @L33tH4x0rs97. That will become less and less charming as you age.

Once you’ve got a good handle it’s time to start following some folks. There are a number of good lists out there for people to follow in infosec. Use one of those to get you started, and then adjust to taste.

Engage in conversation. Don’t force it. Don’t overextend when you aren’t knowledgeable. But if you have something to add then feel free to contribute. It doesn’t matter if you have 3 followers and they have 10,000. Twitter is a meritocracy. And if it isn’t, pretend it is.

One good way to get started is with retweeting content you like from others. As you become more able to add value yourself you can start alternating between retweets and your own original content.

Don’t take it too seriously. Many top security folks on Twitter ramble on about nothing 90% of the time. Others only post pristine content. Just be yourself and it’ll come through. And if it doesn’t, and you feel like you’re doing it all wrong, don’t worry about it. Keep to the above and you’ll be fine.

Social media

There are a ton of other social media outlets. The other big one you should care about is LinkedIn. Have a profile. Put effort into it. Keep it updated. And only connect with people who you either know or who you’ve had at least SOME interaction with. Adding everyone dilutes the power of the network for you and others.

It’s easy to do too much with social media. Resist that. Focus on your website and Twitter, with some LinkedIn thrown in. I keep Facebook mostly separate, but that’s my personal preference.

And remember—everything starts with your website. Create content there, and then blast it out via Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and whatever other channels you use. But don’t create there first.

On Certifications >

I get so many questions about infosec certifications. So many. They come in two forms:

Are infosec certifications really worth it?

Which ones should I get?

Good news: I have answers.

Yes, certifications matter. And so do college degrees. And so does experience. And so does anything else that people think matters.

Things have the value that others place on them.

Certifications don’t have any inherent value. They’re worth precisely as much as people think they’re worth. If employers are asking for them at places you want to get hired, they matter. If the places you want to get hired don’t care at all about them, they don’t have value there. It’s that simple.

But for beginners, yes, they matter.

Which certifications to get

Let’s do this by levels:

Beginner certs

If you’re just starting out, I recommend you get the following certifications:

A+

Network+

Linux+

Security+

No, I don’t work for CompTIA. But thanks for asking.

In this case I’m not saying that these certs have tremendous value except for the most novice of beginners, but there is value in the study.

Like I mentioned in the education section, certifications have good study materials, and if you get all four of these certifications you will have a decent understanding of basics.

Advanced certs

I like to explain infosec certifications like so: You need your CISSP, you should get an audit cert (CISA/CISM), and you should get a technical cert (SANS). So:

CISSP for anyone who wants a career in security

CISA/CISM for all-around security people who want to become managers

SANS (GSEC/GPEN/GWAPT) for technical people

OSCP for penetration testing oriented people

Once you have four years of experience in information security, you should have your CISSP. It’s the closest thing to a standard baseline that our industry has. It’s actually better than a computer science degree in a lot of organizations (because so many aren’t learning anything in their time in university).

Next you want to cover the audit space, which is a critical part of infosec. Get your CISA or CISM for that.

And finally you want to get one or more technical certifications. I recommend starting with the GSEC, which is surprisingly thorough. From there you can branch into GCIA or GPEN or GWAPT based on your preferences. But if you just get the GSEC that would be a good way to round out your food groups.

OSCP and CREST are the most respected certifications for hardcore penetration testers, so definitely start thinking about those if that’s your interest.

Then there’s CEH. It’s there, and people sometimes ask about it, so you might as well get it just to have it. But don’t brag about having it—and especially not around seasoned security people.

Network with Others >

Keep in mind you can do many of these steps in parallel.

Alright, so now we have some education, we’ve got a lab going, we’re working on some projects, we’ve got our website and Twitter popping off, and we’re papered up.

Cool.

Now you need to reach out and talk to some folks. Again, you can and should have been doing this all along, but if you haven’t been it’s definitely time to do it.

Watch who’s coming to your website. Watch Twitter for interesting interactions. Reach out to those people. Start conversations. Go to where they’ll be and interact with them in person. Go to Vegas for Blackhat and DEFCON week. Lots of infosec people there to talk to.

Find a mentor

This one is almost worth its own section, but I’ll just put it here. Find someone who has a style that you like and ask them to mentor you. Email them. Call them up. But do our research beforehand. Make sure you’ve done the stuff in this writeup first.

To get the best response from a potential mentor, make it clear in your first interaction that you’ve put effort in upfront.

Make it as easy as possible for them to help you and you’re not likely to be turned down. One thing I’ve seen in infosec is that people are extremely willing to help others who are eager to work and are just getting started.

Offer to intern

Offer to intern with someone. Offer to do their dirty work. Write scripts for them. Edit their blog posts. Help them sift through data. These things can help, and may lead directly to an interview or other type of hookup for you in the future.

Conferences >

Conferences are a way to do a few things in the industry:

See what new research is being done

Catch up with your other infosec friends who live far away

Present your own thoughts, ideas, and research for others to consume

For #1 you really don’t have to go to a conference. Most talks—especially the really good ones—are made available immediately afterward, so you can just pull them off the website.

That doesn’t help with #2, though, and most infosec veterans after around 10 years on the scene are mostly going to conferences to see their friends. The talks basically serve as a setting for doing so rather than the centerpiece—especially since they can just get the talks online.

But for newcomers to the field talks can be an invaluable way to learn about the infosec culture. Here are a few I’d recommend considering:

If you’re just starting out, you should definitely go at least once to DEFCON. It’s basically a parody of itself at this point, but that’s just because it’s become so popular. Victim of its success and all.

Before DEFCON every year is BlackHat, which is a bit more corporate (and expensive), but is also still decent for new people to attend.

Veterans in the field are starting to avoid these more and more each year, and are instead going to smaller cons that have the feel of old DEFCON, e.g. higher quality talks, a smaller venue that facilitates more intimate discussion with other participants, and…well, just fewer people.

A few of these include:

DerbyCon

ShmooCon

ThotCon

CactusCon

HouSecCon

…and others.

My new favorite conference type are more TED-like single-track conferences that focus on presenting ideas as opposed to just new ways to break things. We need that breaker content, to be sure, but we also need to hear more about overall concepts and how to actually fix things.

I’m particularly enamored with ENIGMA, for example. The single-track model is the way to go in my opinion.

In addition to these traditional types of conferences, you should be signing up locally with your OWASP chapter. Start by just attending the meetings and soaking everything in, and then offer to volunteer to help out, and then—when you’re ready—ask to give a talk yourself.

You want to do the same thing with BSides in your local area. BSides are basically the alternative to major conferences in any given area. The biggest one is in Las Vegas and corresponds with the BlackHat/DEFCON event.

Bottom line for conferences:

Start local, participate, and try to give your own talks as soon as you’re ready

If you’ve never been to a conference before you should probably do DEFCON at least once

The smaller but popular conferences like DerbyCon and ShmooCon are generally considered "better" by most at this point, but that’s a sliding bar that moves with time based on popularity and exclusivity

Remember that the primary benefit of cons is networking and seeing your friends in an infosec setting

Making Contributions >

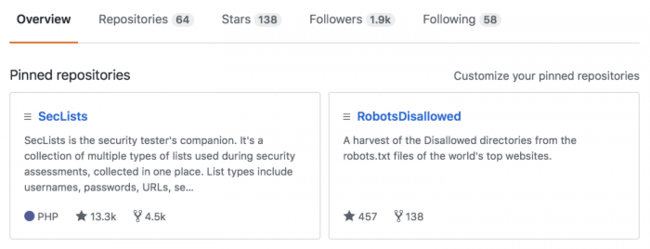

Another great way to enhance your career is to use your skills to help out on various projects.

This is typically done using your programming skillset, and the key is to find things that align with your interests and your work. You don’t want to force this step, or any of them really. Do what comes natural.

A good way to get started is to simply notice, for the tools that you use and enjoy, if they have any outstanding bugs or issues. Reach out to the creator(s) of the tool and ask if you can help.

Github lends itself well to this type of interaction because of pull requests, which allow you to fix something which they can then bring into the project if they like it.

Hey there, I love the project and I have an idea how to fix this issue. Could I code up my proposed solution and send you a pull request?

99% of project leaders will jump all over this, and likely mention you in the credits as well.

It’s good practice for you

It helps improve the tool

You’ll help the project leader out

You’ll get your name out there as an active programmer

Even if you’re not helping in a technical way, there are all sorts of ways to help out projects. You could help organize input, create documentation, get the word out about the project, etc. Find things you care about and help make them better

Don’t chase credit or recognition. Make it about the output and let everything else come naturally.

Responding to CFPs >

Closely related to mastering the conference scene is actually speaking at those conferences. And in order to do that you have to get familiar with the Call for Papers (CFP) game.

If you visit any conference website you’ll likely see a link for speakers, or for CFPs, and this is where you can find out how to submit. You can also subscribe to the conference’s email list and get notified as soon as a CFP opens as well.

Basically, conferences run on talks. Good talks. With good speakers. It’s the lifeblood of any good event. So every year, a few months before the event happens, the conference will open up their CFP, or call for papers, which is how people submit talks for consideration.

It’s called a call for papers because the whole concept comes from the academic space. In that context it’s a bunch of Ph.D.’s or grad students submitting actual academic papers to a specialized conference (like the Peruvian Butterfly Mating Symposium) that are highly specialized, full of citations, and unlikely to be of interest to anyone outside their narrow field.

Information Security has borrowed the concept, but the rules are far more relaxed. First of all, people aren’t submitting academic-style papers in most cases. They’re talks. Presentations. Slides, really.

Here are the things you’ll need to have to be able to submit:

A Great Title: Conferences have tons of talks, and it’s hard to get peoples’ attention. So you have to have a pithy title. Something that is concise and descriptive. One example that I might soon present with a friend is, "From WTF to CTF: How to Become an InfoSec Force of Nature in Less Than 2 Years." That will likely get some people in seats.

A Decent Abstract: The abstract (again, from the academic world) is where you give a basic summary of what you’re going to be talking about. You need to really nail this, as it (combined with the title) is where the review committee is going to make the decision on whether or not to accept you. Depending on the conference this should be 1-5 paragraphs. Be sure to have the following: a basic description of the idea or concept, examples of what will be covered, and what people will get out of it. Be sure to mention if there are any demos or handouts. Conferences love those.

A Deeper Description: Some conferences require you to provide a much more detailed description of the talk. What the sections are. What the demo will cover. Etc. You should have that available if you’re going to be submitting to conferences that require it, but in most cases you’ll be able to get by with a decently descriptive abstract.

Your Bio: You’ll always need a bio. You should have one handy. See the speaker’s bundle section below. You might want to have a couple of bios available. A real formal one that talks about yourself seriously with lots of references to your work. And perhaps something more fun and light-hearted for more technical or hackerish conferences.

A Headshot: You’ll often need a picture of yourself to send in with the talk. Make sure to have a few, so you can customize it for the type of conference you’re speaking at. The headshot will likely be different for RSA or some government conference than for DEFCON or Shmoocon.

The speaker’s bundle

I recommend you create a speaker’s bundle that has all of these:

Bio(s)

Headshot(s)

Talks (have this for each one)

Title

Abstract

Description

Have these stored somewhere so you can quickly copy and paste into CFP forms for various conferences as needed. It really sucks to miss CFPs because you couldn’t get organized fast enough.

Have this stuff ready to go. Conferences happen throughout the year, which means that once you get into it you’ll likely be submitting to at least a few cons per quarter.

Landing Your First Job >

As I talk about in this piece here >, there’s a weird thing happening with jobs in InfoSec/Cybersecurity. Employers think there are no candidates, and people looking to get into the field think there are no jobs. And they’re both right.

People are quite confused about this paradox, but it turns out to have a very simple answer: there are no starting positions—only intermediate and advanced.

Entry-level positions don’t really exist in cybersecurity.

In order to be useful to a team you have to be useful on the first day, and that requires you to have some combination of these three things:

A degree in CS and/or something InfoSec related.

A good set of certifications that show knowledge similar to a degree.

A body of practical, tangible project work that shows you can actually do the things you’ll be asked to do on the job.

For most people reading this, #1 isn’t an option for you at this moment (otherwise you’d already have a position). So you’re most likely going to need a combination of #2 and #3.

See the Certifications section in this article regarding certifications.

For real-world work, you’re going to need a blog, a GitHub account, a Twitter account, and most importantly—you’ll need to find or create projects you care about and actually produce code around them.

Here’s an example > of one of my projects that someone could come up with minimal programming skills.

You don’t have to be a full-stack developer, but you need to be able to program. You have to be able to create things. Maybe it’s automating a workflow. Maybe it’s creating a new tool. Maybe it’s making a better version of a tool that has gone stale.

Whatever—just get out there and create.

Know the job

The next thing you need to be able to do is show that you are actually skilled in the tasks that you’re likely to be asked to do. Based on almost 20 years in the industry, here’s a list of some of these tasks.

Managing Security Appliances / Services: One of the first things you’ll need to do is manage a security appliance/cloud service, such as a firewall, IPS, etc. Know what it does. Know how to configure it (which you’ll have to read the manual and watch videos for). Make it log centrally. Configure reporting to be able to show value from the purchase.

Responding to Security Questionnaires: This is something that every security team has to do, and it’s generally a dirty job that requires a lot of technical knowledge, experience, and the ability to be…um…creative. If you’re able to help the team with this you’re worth a slot on the team already.

Doing Product Evaluations: Management often asks the team to implement X type of protection, whether that’s endpoint defense, cloud WAF, deception technology, AI SOC augmentation—whatever. You need to be able to find the top vendors, create a rating system, perform the evaluation, and then write up a recommendation for management based on your research and the output of the eval.

See this article > for more details on this critical skill.

Write a Quick Script: There will be many times on the team when you need to pull data from someplace, do something to it, and get the results to put into a narrative. Data constantly needs to be pulled, massaged, and presented. Having this skill gives you a major advantage.

Performing Security Reviews: For various reasons, you will often be asked to evaluate the security of a website, a company we’re about to buy, or whatever else. You need to be able—as a non-expert—to do a cursory look at whatever it is and make a very quick evaluation.

This is a short list, and I’ll keep adding to it as I think of more. But what I find so interesting about it is that it shows why there aren’t junior cybersecurity positions. These all require significant schooling, training, experience, intelligence, or some combination thereof.

If you as a candidate can show in your interviews that you can do these things, you’re far more likely to be hired.

A common denominator in almost all of them is strong writing skills >.

Mastering Professionalism >

Ok, now we’re entering the advanced arts. This is the stuff that will take you out of the middle tech areas into the land of the guru and the leader.

Professionalism is the packaging that you use to present yourself. Failing at this means your content can be world-class and you can still go unnoticed or be passed over. Here are the basics:

Dependability. Don’t make commitments you don’t keep. Don’t miss meetings. Be early, not late. Don’t miss deadlines for projects. Under-promise and over-deliver.

Wardrobe. Build yourself a decent wardrobe. Drop the t-shirts. Drop the gym shoes. Get yourself some quality jeans (dark) and some quality shoes. Invest in some decent dress shirts. Make sure everything fits well. And buy a couple of jackets to wear with your jeans; they are an exponent, not a multiplier. Finally, have at least one good suit for when it’s needed.

Speak concisely. Be clear and crisp with your verbal communication. Don’t linger on points. Get them out cleanly and stop so the other person can reply.

Tighten up your writing. Learn and implement this >.

Learn to present. Public speaking is a beast for many people, but if you can’t present you’ll be severely limited in how far you can advance. I recommend Toastmasters for anyone who has significant issues with the prospect of getting in front of people.

These skills magnify everything else you do, and you’ll be surrounded by people who are woefully unskilled in one or more of these areas at all times. Be the person who’s strong in all these areas and you will show well in most any situation.

Understanding the Business >

This is a facet of development that many (most?) technical people lack, and it severely limits their ability to participate in conversations above a certain level.

Here’s the basic rule: For the business, everything comes down to money. Money in, money out. So all the work you’re doing with your risk program, or your vulnerability scans, or your new zero-day exploit—that’s all way below the area of focus for the business.

Businesses want to quantify risk so they can decide how much should be spent on mitigating it. You should be prepared to at least think about how much risk is present (in dollars), how much money it’ll cost to mitigate that risk in various ways, and what (if any) residual risk will remain.

This is extremely hard to do, and you don’t want to do it in a false, pseudo-scientific way. But you need to realize that every security decision is ultimately a business (and therefore money) decision. That’s a maturity marker for InfoSec people.

Some people accept this at some point and keep advancing, and others reject this outright and spend the rest of their careers flipping tables.

In short, try to have numbers for things whenever possible, and try to think in terms of risk and business impact as opposed to specific vulnerabilities and other details.

Having Passion >

Up until now we’ve been talking about the tangibles. Now let’s talk a bit about the other—and arguably the most important—key differentiators between someone who gets to the top of this game and who fades out in the middle.

Curiosity, Interest, and Passion.

90% of being successful is simply getting 100,000 chances to do so. You get chances by showing up. By spinning up that VM. By writing that proof of concept. By writing that blog post. And you have to do it consistently over a number of years.

You can do this two different ways:

Inhuman amounts of self-discipline enable you to do this

A deep, innate passion compels you to do this

Not many people can maintain the first one for that long. It’s hollow. It’s empty. These types are out there, but they often burn out and move on to something else. The top people are compelled.

Most who stay with infosec for many years, and who are successful, achieve success because they’re powered by an internal molten core. They couldn’t stop doing security if they tried.

They’re up late at night writing a tool or a blog post not because it’s the scheduled time, but because they’re physically unable to do otherwise.

Ideally, someone wishing to succeed in this world of infosec should have a lot of self-discipline. It’s important. It’s respectable. You need a certain amount of it.

But if you truly want to thrive, and do so without a frozen soul, you should be pulled by passion rather than pushed by discipline.

Becoming Guru >

Ok, so now you’ve done all this. You’ve got a ton of experience, you’re in your 30’s, 40’s, or 50’s, and things are looking good. What does the top tier look like? What are the top information security people able to do that others are not?

First of all, they usually have all of the stuff we’ve already talked about. But they have additional dimensions that set them apart. Examples include:

Financial knowledge. The ability to handle budgets, understand startup financing, make purchasing decisions, etc.

Management experience. Managing projects and managing people are two distinct things, and people at this tier are good at both.

An extensive network. Many at this tier know a good percentage of the major players in infosec and business.

Dress/Ettiquete. Players at this table have significantly upgraded wardrobes, manners, etiquette, and enjoy more refined leisure activities, e.g., golf, skiing, boating, etc.

Advanced education. Having a master’s degree at this tier is a good idea. It’s not essential, but many top-tier positions do look for university degrees as a checkbox qualification.

Media savvy. Be trained and capable of speaking with the media about various topics.

The Tech/Business Hybrid. People at this level are able to go into a room of developers and help them, jump on a call with a Fortune 50 customer, update the board on a key issue, and then do an interview with a media source. Understanding different audiences and each of them needs is key.

Creativity. Those who make it this far are expected to come up with new ideas and approaches to problems on a regular cadence. It’s not enough at this level to simply execute on what you’ve been given. You have to be able to innovate.

Reversing the interview

There’s something else that top security people often do after they’ve seen and done quite a few things in the industry:

They start thinking more about how they can change the world, and less about what the company is giving them.

So instead of asking about the 401K, or about vacation, or salary, they’re more likely to ask how much support they’ll have in the organization for doing what they think needs to be done. Or they’ll start only taking jobs where they feel they can directly impact security in a tangible way.

Top candidates are having conversations as opposed to being interviewed.

Basically, after a certain level of experience and success, some small percentage of security professionals will decide that there’s (almost) nothing a soul-crushing company could give them that would make them want to work there. And at that point they will only take jobs where they feel like they’re making an actual difference.

Not everyone gets to that point in their career, and not everyone necessarily should. But it’s an important distinction in perspective: are they still working to get more from the companies they work for, or have they transitioned to caring more about their impact on the industry?

Summary

I hope this resource is helpful to people as they enter and move through the various levels of a Cyber/InfoSec career.

It is a journey for sure, but a worthwhile one.

Notes

Be sure to catch the sister post to this one, by Lesley Carhart (@hacks4pancakes) >. She has a brilliant guide > on the different career paths you can take within information security. Highly recommended!

If you have any feedback on how to improve what I have here, please let me know on Twitter or in the comments below, and if you have any specific questions on how to navigate through the maze, feel free to reach out to me directly.

Remember that the farther you get into your career the less any education or certifications matter. It all becomes about what you’ve *done*, which is how it should be.

Thanks to my friend Jason Haddix > for reading versions of this.

The ability to be focused on one’s impact on the industry also requires a certain level of confidence and/or influence that few have, otherwise the person will simply feel like a tiny cog that cannot possibly affect change. This is another reason only experienced and successful people tend to make this transition: they’re the only people who believe they can actually make a difference.