We Were Very Wrong About Testosterone

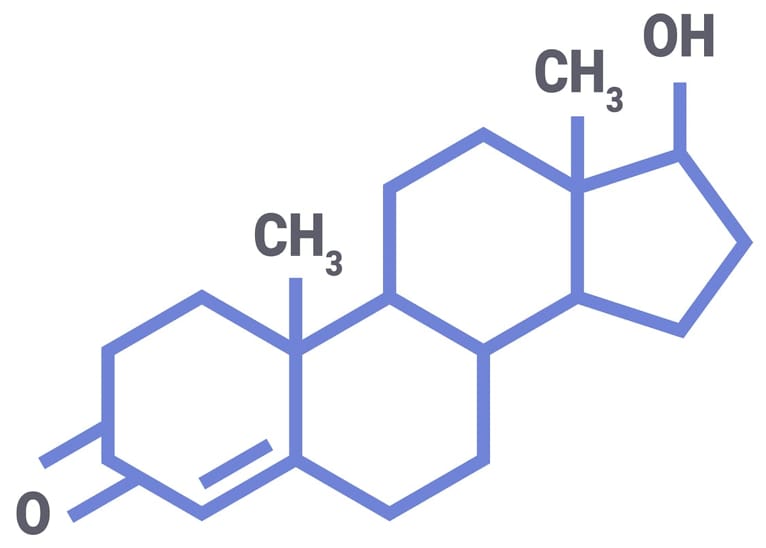

I’ve always been told that testosterone was the hormone for aggression, violence, and…basically…maleness.

Food pyramid anyone?

But after decades of being surprised by bad science education, I’m still surprised about how wrong this was. The first I heard of a different understanding was in Robert Sapolsky’s book, Behave >, which I read a couple of years ago.

Like the myth that the tongue has different regions for taste, the idea that Testosterone is a violence hormone is bad science that won’t die.

Sapolsky is a neuroendocrinology researcher at Stanford, and his comments in Behave just blew me away.

Testosterone makes us more willing to do what it takes to take or maintain status.

Robert Sapolsky, Behave >

Robert Sapolsky, Behave >He makes this statement after thoroughly describing how the previous studies were just really bad that linked it directly to violence, and then goes on to describe how if the game were to be about giving, testosterone would encourage someone to be more giving. Speaking of a game where people were being tested on how generous they were, he says this:

And what happens when people were given testosterone beforehand? People made more generous offers. What the hormone makes you do depends on what counts as being studly.

Robert Sapolsky, Behave >

Robert Sapolsky, Behave >This is monumental, and he ends that section with an earth-shattering and concise analysis:

In our world riddled with male violence, the problem isn’t that testosterone can increase levels of male aggression. The problem is the frequency with which we reward aggression.

Robert Sapolsky, Behave >

Robert Sapolsky, Behave >Since reading that book I’ve heard multiple other accounts of testosterone from scientists that—at the very least—obliterate the commonly-held characterization of it being purely violence-focused.

Huberman also has a great podcast >.

Then I recently heard Dr. Huberman > speaking on Led Fridman’s podcast about health and diet and such, and he simplified it in a fascinating way. He described the hormones like this:

Huberman didn’t characterize Dopamine and Serotonin this way, but it’s an accepted simplification.

Prolactin makes people lazy

Testosterone makes effort feel good

Estrogen makes emotion feel good

Serotonin makes us generally feel good

Dopamine makes achieving goals feel good

The major effect of testosterone is to make effort feel good. That’s what testosterone does.

Dr. Huberman, Stanford Neurobiology Lab

Dr. Huberman, Stanford Neurobiology LabI notice both Sapolsky and Huberman are at Stanford.

That’s remarkably similar to Spolsky’s characterization, but even further abstracted to effort rather than just status.

Anyway, I just find it fascinating that I’ve had the wrong impression about testosterone all this time. That most of us have.

This new framing is really positive to me. It helps explain why I get so much joy from grinding away towards my goals, and provides a possible hint for a larger conversation around several trends in the last 3-5 decades, including: increasing depression, falling birthrates, people having less sex, and reduced sperm counts.

Maybe we’re suffering from a lack of the immigrant mentality > that made America so prosperous, which is producing some sort of cascading failure in striving, acheivement, and happiness.

That’s a book I’d love to read.