Thoughts on Prompt Injection OPSEC

I want to respond to this blog post that's arguing that prompt injection strings are essentially zero-days that we should not share with attackers.

I'll start by saying that the author seems genuinely concerned that harm is being done, so I appreciate the piece from that standpoint. We need more people in this debate, not fewer, and I appreciate anyone in the arena.

But I don't think the fundamental claims are correct, and there seem to be competing sources of criticism beyond just the public safety concern.

Security Theater?

We'll start with this one, which seems quite extreme.

Not only is "AI red teaming" mostly security theater, but it actually makes systems more vulnerable.

How?

Because of the game theoretic constraints introduced by the mathematical realities of the underlying system architectures.

First, a lot of things can be said about the AI Red Teaming / Security space, but I don't think Security Theater is one of them.

We know AI adoption is happening faster than any previous tech. Time to 100 million users:

- ChatGPT: 2 months

- TikTok: 9 months

- Instagram: 2.5 years

As UBS analysts put it: "In 20 years following the internet space, we cannot recall a faster ramp in a consumer internet app." And McKinsey reports that 78% of organizations now use AI in at least one business function—up from 55% in 2023.

This is resulting in an extraordinary number of new applications—enterprise apps, startup apps, hobby applications, and everything in between.

Many of these applications have AI front-ending the system in the form of one or more agents, or at least some sort of AI as part of the flow that processes inputs.

This is an acute and time-sensitive security challenge. The fact that AI Pentesting and Red Teaming and overall security services exist is not, to me, in any way security theater.

2. What does this mean?

Then we have this to back up the security theater claim.

...because of the game theoretic constraints introduced by the mathematical realities of the underlying system architectures.

That reads to me like someone trying to stop me from debating them because they're smarter than me.

But they ask for grace, so let's give it to them.

Disclosing the attacks–like prompts–that were successful against any system does nothing to make anyone safer. In fact, it makes things considerably worse. The key to understanding why lies in two important facts: First, these attacks are not patchable. There is no security fix.

Even if something can't be fixed completely doesn't mean there isn't value in defenders understanding how attacks are carried out in the real world.

There are mitigations. There are controls. Even if they're not foolproof.

Hardening against one prompt or even 50,000 prompts likely leaves a nearly infinite amount of variances unpatched.

Yes, but no security is absolute—regardless of domain. The question is whether we're tangibly reducing risk by learning how the attacks are done and putting defenses in place.

3. This argument sounds familiar

Then we have this bit, which is getting to the main issue I have with the post.

Prominent "AI red teams" put libraries of prompts right out on the open internet. Proudly. For anyone to use.

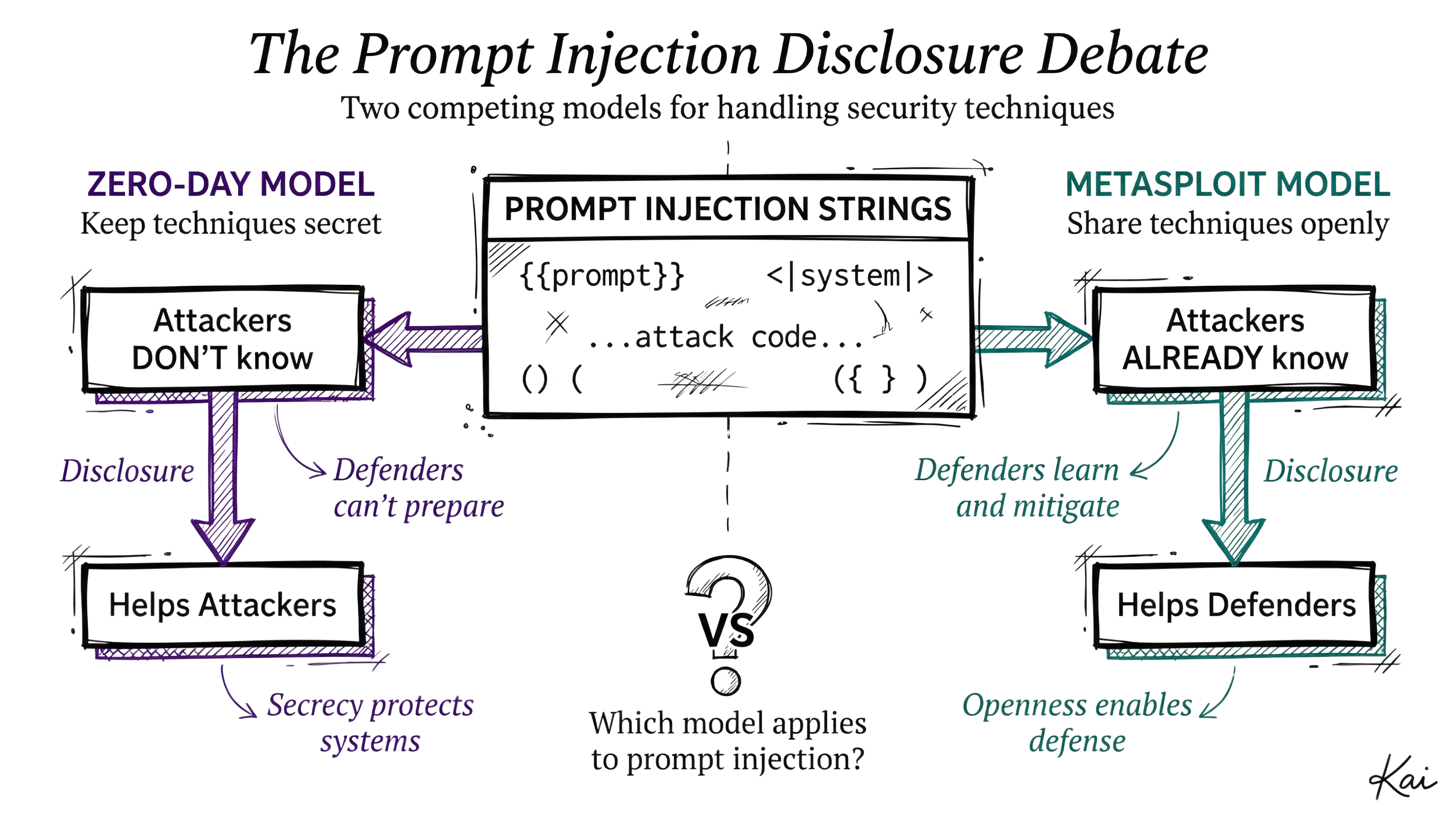

This is the same argument that people made against releasing Metasploit and similar tools.

Basically, "If we talk about how we get attacked, it will just help attackers."

I had my AI system go and do a whole bunch of research on this, and while the results were mixed, the data definitely pointed in the direction of information helping defenders more than attackers.

So it seems to me that the burden is on the author to describe why prompt injection is specifically different than other types of offensive technique sharing.

Like I said above, I don't think the fact that it's unpatchable is the answer there. Because controls can still mitigate a lot of the risk.

4. Attackers already know

Here they are arguing that they are using the knowledge from the published prompts and building their own system.

My argument around this has been since 2023 that it's going to get easier and easier to do these attacks the better AI models and scaffolding becomes.

And our paper shows that these attacks will never stop popping up. The prompt gives you a start. Math gives you the plan. Infinity is now manageable, and time is on your side ... You pick one prompt, and iterate. That's it. ... That "defended" prompt just became the key that lets an attacker into the entire system.

Potentially true, yes.

But it's not as if the attacker was completely lost and had no idea how to do this using AI themselves.And then the AI red teaming community released the prompts, and now they are able to do the attacks.

Anybody who's wanting to launch these attacks, especially at scale against sophisticated defenders, has already known for a long time how to create an engine that combines attack strings in a combinatorial and/or iterative way that can be automated.

And it's only getting easier and easier to make better and better automated AI attack engines like these. At this point I and many others can one-shot a prompt that builds such a system. We're not telling most attackers—especially the good ones—anything they don't already know.

5. Coming right out with it

And now temperature increases on the language.

If you maintain a public repo of prompts you use to test, you are endangering every client you ever had.

First off, there's a difference between public prompts and the prompts that have worked against customers. Or at least there should be.

I am in this space myself and I have many friends who do AI Security Assessments multiple times a month. They are all very careful to keep specific prompts that worked against actual customers out of anything they release publicly.

They might share the techniques, or the cateogory, or talk about it if it's a new class of attack or something, but they're not copying and pasting actual customer attack strings to Github.

6. Over the line

And finally:

If you paid for an AI red team to assess your AI security, they are likely your biggest AI security liability.

I guess given the context above, the author is basically saying that if you have a security company that you presumably trusted enough to bring in in the first place, if you have them look at your AI systems, they're going to take the exact prompts they used and publish them directly online.

That is an extraordinary claim to make, and as I said above, I know it not to be true for myself and my friends who do this work.

7. Something else entering the conversation

You, a celebrity “AI red teamer” did all my work for me.

And here we see some definite noise in the signal they're trying to transmit.

This is starting to feel a lot more like an attack on one or more specific individuals and their "celebrity", rather than a security discussion.

My take

If I were to steelman the argument being made, which I am again thankful they brought up...I would say something like:

Prompt injection strings are more like zero-day exploits than Metasploit modules because there's no absolute patch for them. And attackers can move much faster than defenders.

I think this is a (nearly) decent argument because the security community already agrees that zero-day exploits should not be released immediately to the public, even if researchers and/or defenders have them in hand.

So then the burden is on the counter-argument to say why prompt injection strings are not 0days.

But I don't think the analogy holds for a few key reasons:

- It's highly valuable for defenders to understand how these attacks are performed because it will inform their defense

- While those defenses will never be 100%, even 50-90% is still significant risk reduction

- We are extremely close to any attacker being able to one-shot extremely dangerous automated prompt injection frameworks—or at the very least the ability to programatically combine attack techniques and strings

In other words, the argument hinges on 1) prompt injection strings being zero-days, and I don't think they made a strong enough case to show that, and 2) attackers being in the dark without researchers / red teamers showing them the way.

I think both of these are mistaken.

I also think the argument would have been stronger if it didn't include morality-based attacks on the people doing this AI Red Team work.

Do the AI red teams” do this because they don’t understand what they’re doing? Or is it because they just don’t care?

I am not a mind reader, so I won’t pretend to know.

They said that, but then proceeded to do that very thing...

And as a security professional, I feel it’s a matter of morals/ethics/whatever you want to call it to put the client’s OPSEC before my need for ego validation.

If you maintain a public repo of prompts you use to test, you are endangering every client you ever had.

Full stop.

Final thoughts

Anyway, interesting topic with some obvious strong opinions involved.

Eager to hear what others think, one way or the other.

Notes

Cox, Disesdi Susanna. "AI Red Teaming Has An OPSEC Problem." Angles of Attack: The AI Security Intelligence Brief, November 24, 2025.

"ChatGPT sets record for fastest-growing user base." Reuters, February 2, 2023. UBS study citing Similarweb data.

"The State of AI." McKinsey & Company, 2025. Annual global survey of 1,000+ executives.

"Offensive Security Tools: Net Effects Analysis." Substrate Research, November 2025. Research performed by Kai (Daniel's AI system) using 64+ AI agents in parallel adversarial analysis (32 specialized agents per argument position across 8 disciplines: Principal Engineers, Architects, Pentesters, and Interns), analyzing 24 atomic claims per position through structured red-teaming methodology.