Those Bashing Smart Locks Have Forgotten How Easy it is to Pick Regular Ones

There’s currently a major backlash in the InfoSec community against so-called "smart" locks.

And it’s not just by people who naturally overreact to change, or from people outside of InfoSec: there are plenty of smart people in our field—whom I respect greatly—that are making loud noises against this technology. So I want to make it absolutely clear that 1) there are smart arguments on both sides of this discussion, and 2) I’m still open to being wrong about this.

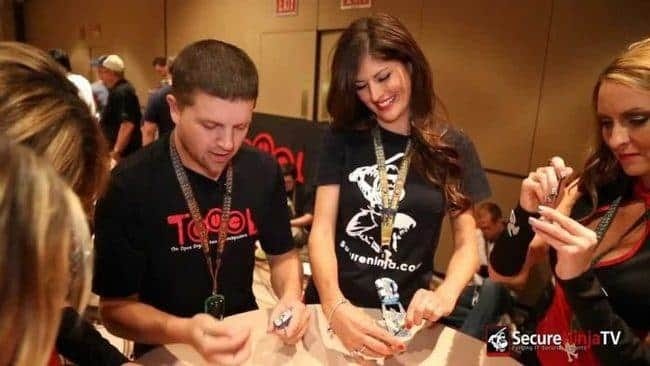

People picking locks at an Infosec event

My main argument isn’t that smart locks are great security, or that IoT security is fine, or that the new is always better than the old—or any of that garbage. I lead The OWASP IoT Security Project >—-which details precisely how insecure IoT systems can be, and I’ve personally been finding these kinds of flaws in real devices for over a decade.

IoT Security is still a garbage fire, and we’re just starting to get our collective arms around the heat and smell of the problem. So you’re not going to hear the "IoT Security is Great" argument from me. What you’re going to hear from me is an appeal to practicality and risk management by asking a very simple question:

What’s easier for your most likely attacker to bypass—a regular lock, or a smart lock?

I’m not a lockpicking expert, by the way, but that’s kind of the point. You don’t have to be to get past most locks.

Many people in InfoSec have been to security conferences where they’ve learned in a matter of minutes how to open most locks with basic lockpicks. And once you’ve practiced for any period of time you can open the most commonly used house locks in mere seconds. And that’s not even talking about bump keys >, snap guns >, or any of the other more advanced techniques that are now available.

I’m not saying smart locks have good security—I’m reminding people that regular locks have virtually none.

The problem I see in this discussion is that we’ve somehow—in the information security community—forgotten about the risk that we have already accepted. For hundreds of years we’ve protected our homes and businesses with lock technology that’s absolutely trivial to bypass for anyone who spends even the slightest effort.

Threat modeling brings reality into focus

This is why threat modeling is so important: it allows us to move away from the open-ended theoretical discussion and into the world of the scenarios you’re most likely to face. So let’s do a few scenarios and see where we end up.

I honestly ran through this threat model not knowing where it would take me, which is why they’re so valuable.

You live in a middle-class neighborhood in Middle America, most of the people in the neighborhood are teachers, cops, DMV workers, and just regular folk. There’s very little violent crime, but there have been some home break-ins recently due to the opiate crisis.

You live in a high-tech housing area in a big city full of the smartest tech workers in the world, e.g., one of the Facebook housing units in Menlo Park, or a similar place in Seattle or Austin.

You live in a very established and nice neighborhood with an active neighborhood watch, where everyone knows everyone else, and all crime is very rare.

You live in a high-property-crime area in a big city. It’s supposed to be getting better soon as people work on clean-up efforts, but cars and homes are getting broken into often, with people finding things stolen, drug paraphernalia left behind, etc.

I think these are decent approximations of the bulk of people’s living situations in the United States. So for each of these attack scenarios, let’s ask ourselves: who the attacker is, how they’re getting into the house, and whether they’re going to have more, less, or equal success facing a regular lock or a smart lock.

I’m also not a property crime expert, so feel free to correct me if you are.

Now let’s model some attackers:

Drug-addicted, looking for anything to sell or trade for opiates

Mid-tier professional thieves who go after mid-tier neighborhoods for TVs, computers, jewelry before moving on or getting caught

High-end professional thieves who go after jewelry, art, and the content of safes

Neighborhood kids looking for opportunities for fun or to find something to sell for quick cash

Disgruntled delivery people

Roving package thieves >

Now let’s start combining these targets with their potential attackers in likely scenarios:

Addict as threat actor

Addicts vs. Middle America: Why not kick in the door or break a window?

Addicts vs. High Tech Area: Why not kick in the door or break a window?

Addicts vs. Super Nice Area: Why not kick in the door or break a window?

Addicts vs. High Crime Area: Why not kick in the door or break a window?

Mid-tier Professional as threat actor

Mid-tier vs. Middle America: Pick the lock, go through window, kick door

Mid-tier vs. High Tech Area: Pick the lock, go through window, kick door

Mid-tier vs. Super Nice Area: Pick the lock, go through window, kick door

Mid-tier vs. High Crime Area: Pick the lock, go through window, kick door

For the mid-tier and above, if everyone in a neighborhood had a basic smart lock with a pin pad set to the same thing or something, that could be a good way in.

High-end Professional as threat actor

High-end vs. Middle America: Mismatched target, unlikely to attack smart locks

High-end vs. High Tech Area: Possible smart lock attacks to steal computers or intellectual property

High-end vs. Super Nice Area: Possible smart lock attacks, but easier entry available

High-end vs. High Crime Area: Mismatched target, unlikely to attack smart locks

Neighborhood kids as threat actor

Neighborhood kids vs. Middle America: Possible smart lock attacks, if it’s trivial

Neighborhood kids vs. High Tech Area: Mismatched target, unlikely to attack smart locks

Neighborhood kids vs. Super Nice Area: Possible smart lock attacks, but risk is probably not worth it

Neighborhood kids vs. High Crime Area: Why not kick in the door or break a window?

Disgruntled delivery person as threat actor

Disgruntled delivery person vs. Middle America: Possible, but they already have tons of opportunity to break the law and steal merchandise every day, and they’re more likely to avoid chances to be caught (logs, video, etc.)

Disgruntled delivery person vs. High Tech Area: Possible if easy enough, since the payoff might be sufficient? But why not pick the lock?

Disgruntled delivery person vs. Super Nice Area: Possible if easy enough, since the payoff might be sufficient? But why not pick the lock?

Disgruntled delivery person vs. High Crime Area: Other options seem better than spending time on hacking the smart lock.

Package thieves as threat actor

Package thieves vs. Middle America: Seems like they’d prefer to pick a lock vs. mess with a smart lock location because smart lock people are likely to have a camera in or around the house.

Package thieves vs. High Tech Area: Seems like they’d prefer to pick a lock vs. mess with a smart lock location because smart lock people are likely to have a camera in or around the house.

Package thieves vs. Super Nice Area: Mismatched target, unlikely to attack smart locks (you don’t go to Beverly Hills to break into homes and steal their Amazon packages)

Package thieves vs. High Crime Area: Other options seem better than spending time on hacking the smart lock.

Whew. Ok. That was fun.

So we did see a few situations where attacking a smart lock could make sense, assuming they were similar enough for it to be quick and easy—like in a housing complex for tech employees (in say 5 years). But in most cases I think this cursory analysis shows that either:

It’s easier to kick in the door or go through a window (or pick the lock) than it is to even look at a smart lock, or…

Attackers are likely to start associating smart locks with video capture, remote monitoring, and lots of other IoT-ish functionality, which will mean a higher risk of getting caught.

Summary

There are smart people arguing against smart locks, and it’s a discussion worth having.

IoT Security isn’t good, and so neither is smart lock security.

We forget the risks we’re used to—and in this case the thing we’re forgetting is now easy it is to pick a lock or kick in a door.

If you run through the scenarios you’re likely to face, you’ll see that very few of them make it easier to get into your home because you have a smart lock, since you either have a threat actor mismatch or the alternatives are simply better for the attacker.

The fact that people with smart locks are likely to have cameras and other smart security technology is likely to become a significant deterrent soon—if it hasn’t already—which will result in more people just moving on to the next home instead of messing with your house.

I think all of this combines to this:

If a smart lock gives you significant features and convenience—above what you get with a normal lock—then it’s likely to be more than worth the risk tradeoff.

This is because it won’t be about replacing good security (old lock) with good security (IoT lock), but rather about replacing no security with something equally bad that’s more convenient and that might be a deterrent as well.

Notes

The front door is bad overall security for a home, and just changing your lock don’t solve that.

To me, the best argument against smart locks is that with a common door you already have the weakness of the existing conventional lock, and if you are still able to access that regular lock mechanism when you install a smart lock then you’ve simply *added* attack surface rather than changed it. In other words: you’ve now combined the weakness of the legacy lock with the weakness of the smart lock, which can only make the overall result weaker.

If you can think of other abuse cases that I haven’t included, please let me know. For example, how to combine the internet vector with the local/physical side.

The other complication with this discussion is that there are many potential combinations of the basic control variables, e.g., the strength of the door structure vs. being kicked in, the ease of entering via windows compared to the door, and the type of crime in the area in question. It’s much different, for example, if we’re defending against young, smart rich kids who might break in and steal the Amazon packages in your foyer while your maid is upstairs, or if you’re defending against frazzled adults looking for meth money.

I’d also say that there are many "smart" locks that are just trivial to bypass because they’re just garbage. And in those cases it just requires that knowledge to take advantage, and there I’d side with them being *worse* for security. But I think those are likely to be spread out and hard to take advantage of.

Another key point is that it’s possible to oppose smart lock implementation without even arguing that they’re easier to bypass. I have a friend/associate who is currently being told that her whole building is being "upgraded" to smart locks, which will be able to log everything and send those logs to some random startup, without her knowledge or transparency. In short, there are privacy concerns in addition to the larger physical access question.