Information Security Resilience

Imagine what would have happened if, on September 13th, 2001, the President of the United States had said the following:

Congratulations on killing 3,000 defenseless civilians. We will cry today for the fallen, but we will continue tomorrow as if this never happened. We will continue to embrace the vulnerability that comes with the freedom we cherish. We are a resilient people, and we lost that many people last year from car accidents.

We will not do television shows about you. We will not write reading about you. Attack us if you will, but you will not harm us; you will only strenthen our belief in freedom and guarantee that nobody will ever know your name."

We, as a society, are focused on the wrong component of the risk equation. Rather than focusing on reducing probability through prevention, we should be reducing impact through resilience.

This 9/11 response above doesn’t make buildings immune to airplanes, but does provide critical resistance to the terror that results from such attacks. This resistance is the difference between a multiple trillion dollar hit on our economy, and a brutal blow to our national psyche, vs. a negative incident that we quickly deal with and move on from.

Cry, pick up, dust off, drive on. Resilience is the defense against terrorism that America needs. Prevention when possible — absolutely — but in an open and connected (see ideal) society we should expect to be successfully attacked, and our best defense is not to deny this unpleasant truth but to simply absorb it when it happens.

Now, imagine what would happen if we handled information security the same way.

Information Security Resilience

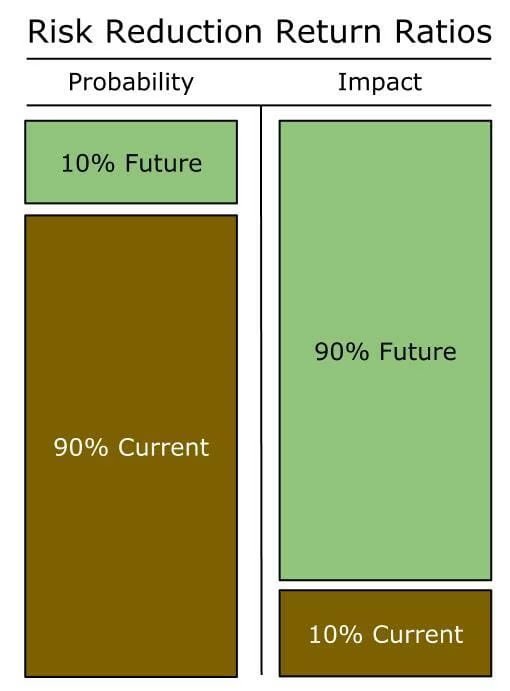

As we all know, there are two main components to risk: 1) the chance that something will happen, and 2) how bad it would be if it did. Or, probability and impact. For the last 20 years, in both terrorism and information security, we have focused on prevention (probability) and this effort has yielded some decent returns. But no longer.

We’ve simply reached Peak Prevention — a wall of diminishing return where we can multiply our efforts by many fold and get no reduction in risk (and perhaps even an increase). 10 years ago we were at 50% prevention maturity, and now we’re at 90%. If we spend another 10 years and 10 trillion we can maybe get to 95%. But all that effort would provide only a small fraction of what we could achieve by making successful compromises less costly.

Imagine if we were to say that digital identities are easy to steal. What if we were to say that social security numbers are already out there, and that they’re not as important as we thought they were. Or perhaps that corporate networks are too massive to perfectly defend, and that breaches are often inevitable.

What then?

Answer: We would move from a paradigm of terror at the thought of a breach, and panic once one has been detected, to that of practiced, mature preparation and controlled response.

In short, we may not be able to lower the probability value much more in the risk equation, but we can absolutely adjust the impact. And if the impact goes down, so does the risk.

In this world, the negative publicity from getting hacked comes only from negligence with controls and/or a poorly handled incident response or notification. As it becomes understood that highly trained, asymmetrically resourced adversaries will penetrate highly complex global networks and do harm, the taboo of compromise is all but removed.

In fact, we’re already starting to see that happen. In the last decade we’ve seen literally hundreds of public breaches, with a staggering number coming in the last few months alone. Some of these companies have been rocked by their incidents, while others are virtually unscathed after just a few short weeks.

What’s the difference?

The Role of Controls

Many who make a living in security probably don’t want to hear hat we’re about to switch to a resilience paradigm from one of prevention, as it seems to almost trivialize compromise.

Nobody will care if they get hacked!

But that’s not true.

The difference between a company that goes on to be successful after a breach and one that suffers immeasurably is that the former had the controls in place and the later did not. And I’m not just speaking of a few technical controls: I mean a robust, highly mature information security program that has not just the technology but also the processes and training to respond properly when something does take place.

So the security industry will be just fine. The difference is that companies who are judged to have done everything right, but still got hacked, will not suffer the shame that is still associated with being compromised. This will become commonplace, and an accepted part of doing business in the 21st century. The stigma is falling away.

The only question will be whether or not you had your shop in order when it happened, and whether you responded appropriately. Consumer confidence in your company, and your stock price, will reflect this truth.

Two Approaches to Reducing Impact

Once we’ve accepted that the future path of risk reduction lies in reducing impact, we can start to look at ways to accomplish that. I see two primary ways to do so:

1. Significantly Reduce the Impact of Common Compromises

This portion of the solution will have many technological components, including an idea I got from recent password compromise issues. I believe the networks of the future will store their data in a decentralized way that makes common compromises virtually useless.

In other words, access to data as a result of a low to mid-level compromise will not yield anything of use to attackers because they’ll only have a tiny percentage of what’s required to make the data usable. And getting the other requisite pieces would require failures across multiple other areas in the company’s defenses.

2. Reduce the Value of the Data That is Stolen

This one is harder, but it’s still doable if enough people are involved and energy is put into it. Examples here could include modifying the requirements for getting a credit card, procuring a mortgage, etc. If additional factors (stronger factors) are added to the equation we could see the impact of SSNs or CCNs being stolen plummet significantly.

Conclusion

However it’s accomplished — and it’ll definitely be through a myriad of approaches — this shift is upon us. We’ve had a good run at catching the prevention unicorn, and we need to maintain our ground and continue to innovate in prevention to some degree. But the true progress in future risk reduction will come from reducing the impact of breaches. The sooner we accept this the better.

Information Security Resilience: let’s get started.