Technical Professions Progress from Magical to Boring

December 9th, 2017

There was probably a time when accounting was the most magical thing in the world. The ability to manipulate numbers and derive truths about the state of things.

Constructing a tall building used to done by what was called a Master Builder, which is someone who could do every piece of the build themselves. The architecture, the foundation, the support structure, the walls and floors—everything. But then buildings became too advanced, and each step in the process had to be broken into sub-steps, and there became specialists in all those different skills.

I highly recommend The Checklist Manifesto.

Once the complexity became too great, the system of connecting all those different disciplines, at the exact right time, had to be done by a series of complex checklists. And at that point it’s just a matter of following an exact procedure (defined in the checklist) according to a standard.

Kind of boring, I imagine. But not so back when there weren’t any checklists—back then it was something special to divine something into being.

Surgeons are basically L4 tech support for the human body.

The pattern I’m seeing here is that in the early maturity of a profession there are no checklists and there are no standards. And because of this we’re all genuinely surprised if anything is created at all. It’s magic every time.

An OG InfoSec Practitioner at Work

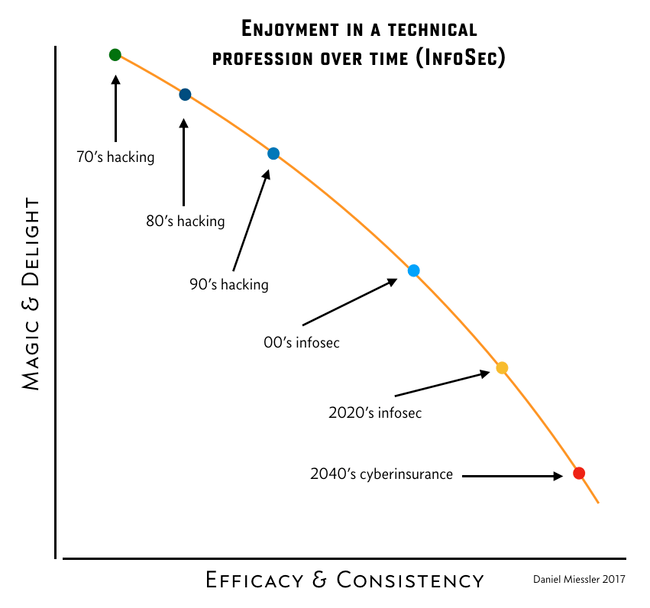

But then, as the profession matures, it becomes more and more about repetition and precision, and the magic gives way to structure. Even more importantly, the goal of the profession is to become more defined, more structured, and—necessarily—more boring.

I find it ironic that I’m talking about checklists becoming important in security’s future, when we’ve spent so long fighting the "checkbox" assessment.

I think we’re getting close to an initial inflection point in the field of information security. It started as magic. Anyone who knew anything about it was—by definition—a wizard. And now it’s increasingly obvious that good security looks a lot like good health, fitness, and hygiene. Like disaster preparedness. And building good software perhaps looks a lot like building a skyscraper with the checklist coordination of dozens of teams.

presumably good pilots using checklists

I think the natural endpoint in all this is that information security will eventually be as exciting as accounting. It’ll be a discipline of nested disciplines, checklists, and easily verifiable states of existence within an organization that can be assessed by other people. Much like a building inspection or a medical exam.

There are key differences between infosec and other fields that will stress the limits of the metaphor.

My key takeaway is that it seems the goal of technical professions should be to become boring. Because boring means mature, and mature means that it can consistently deliver the value it promises. Skyscraper construction does that. Software construction does not.

This also raises a similar point about deep learning: can it truly be dependable and high-quality if you can’t see the variables?

It’s disturbing to me that we basically need to choose between magic and quality. Consistency requires knowing the variables—or at least as long as humans are required to perform the steps. The delight produced by magic comes from the mystery, and that’s precisely the piece that we need to give up.

It’s a strange choice to have to make within a profession you love.

Notes

May 5, 2019 — I had a conversation with my friend Gal Shpantzer today about this post, and he brought up a great point I should have mentioned. I consider this post to apply to—say—2025 and before, e.g., the world in which most of the cyber-suffering comes at the hands of ourselves. Own goals. Stupid mistakes. Negligence. Lack of patching. Failing to have asset management. Etc. Those are PvE games, and we’re losing them because we lack solid accounting practices (and the variables aren’t yet able to be put into accounting terms). Once we can take a data-based approach we’ll be able to handle most of those issues easily. But there’s another type of threat that isn’t PvE, it’s PvP—or—second-order chaos. PvP situations mean that checklists don’t work, because once the enemy knows what’s on the checklist they can simply change their tactics. It’s the difference between a wing-chun dummy and a real adversary. Right now most of our harm comes from the environment, so this essay is 100% applicable. But once that changes, and most risk comes from adversaries, we’ll need a lot more than checklists.

What’s interesting about this is that art doesn’t have this problem. In art you can simultaneously be both a master of a field and a student with fresh eyes every time.