The Difference Between Red, Blue, and Purple Teams

There is some confusion about the definitions of Red, Blue, and Purple teams within Information Security. Here are my definitions and concepts associated with them.

See my article on the different Security Assessment Types >.

Definitions

Red Teams are internal or external entities dedicated to testing the effectiveness of a security program by emulating the tools and techniques of likely attackers in the most realistic way possible. The practice is similar, but not identical to, Penetration Testing >, and involves the pursuit of one or more objectives—usually executed as a campaign.

The best Blue Team members are those who can employ Adversarial Empathy, i.e., thinking deeply like the enemy, which usually only comes from attack experience.

Blue Teams refer to the internal security team that defends against both real attackers and Red Teams. Blue Teams should be distinguished from standard security teams in most organizations, as most security operations teams do not have a mentality of constant vigilance against attack, which is the mission and perspective of a true Blue Team.

Purple Teams > exist to ensure and maximize the effectiveness of the Red and Blue teams. They do this by integrating the defensive tactics and controls from the Blue Team with the threats and vulnerabilities found by the Red Team into a single narrative that maximizes both. Ideally Purple shouldn’t be a team at all, but rather a permanent dynamic between Red and Blue.

Red Teams

See all my Information Security Articles >

Red Teams are most often confused with Penetration Testers >, but while they have tremendous overlap in skills and function, they are not the same.

Red Teams have a number of attributes > that separate them from other offensive security teams. Most important among those are:

Emulation of the TTPs used by adversaries the target is likely to face, e.g., using similar tools, exploits, pivoting methodologies, and goals as a given threat actor >.

Campaign-based testing that runs for an extended period of time, e.g., multiple weeks or months of emulating the same attacker.

If a security team uses standard pentesting tools, runs their testing for only one to two weeks, and is trying to accomplish a standard set of goals—such as pivoting to the internal network, or stealing data, or getting domain admin—then that’s a Penetration Test and not a Red Team engagement. Red Team engagements use a tailored set of TTPs and goals over a prolonged period of time.

Red Teams don’t just test for vulnerabilities, but do so using the TTPs of their likely threat actors, and in campaigns that run continuously for an extended period of time.

There is debate on this point within the community.

It is of course possible to create a Red Team campaign that uses the best-of-the-best TTPs known to the Red Team, which uses a combination of common pentesting tools, techniques, and goals, and to run that as a campaign (modeling a Pentester adversary), but I think the purest form of a Red Team campaign emulates a specific threat actor’s TTPs—which won’t necessarily be the same as if the Red Team were attacking itself.

Blue Teams

The goal here is not gatekeeping, but rather the encouragement of curiosity and a proactive mentality.

Blue Teams are the proactive defenders of a company from a cybersecurity standpoint.

There are a number of defense-oriented InfoSec tasks that are not widely considered to be Blue-Team-worthy, e.g., a tier-1 SOC analyst who has no training or interest in offensive techniques, no curiosity regarding the interface they’re looking at, and no creativity in following up on any potential alerts.

All Blue Teams are defenders, but not all defenders are part of a Blue Team.

What makes a Blue Team vs. just doing defensive things is the mentality. Here’s how I make the distinction: Blue Teams / Blue Teamers have and use:

A proactive vs. reactive mindset

Endless curiosity regarding things that are out of the ordinary

Continuous improvement in detection and response

It’s not about whether someone is a self-taught tier-1 SOC analyst or some hotshot former Red Teamer from Carnegie Mellon. It’s about curiosity and a desire to constantly improve.

Purple Teams

Purple is a cooperative mindset between attackers and defenders working on the same side. As such, it should be thought of as a function rather than a dedicated team.

The true purpose of a Red Team is to find ways to improve the Blue Team, so Purple Teams should not be needed in organizations where the Red Team / Blue Team interaction is healthy and functioning properly.

The best uses of the term that I’ve seen are where any group not familiar with offensive techniques wants to learn about how attackers think. That could be an incident response group, a detection group, a developer group—whatever. If the good guys are trying to learn from whitehat hackers, that can be considered a Purple Team exercise.

Broken Purple Team analogies

I have some analogies that I came up with for describing how the concept of a dedicated Purple Team is a bad idea.

Waiters Who Don’t Deliver Food: A restaurant is having trouble getting their waiters to pick up food from the kitchen and bring it to tables. Their solution is to hire "kitchen-to-table coordinators", who are experts in table delivery. When management is asked why they hired this extra person to do this instead of having the waiters do it themselves, the answer was:

> The waiters said it wasn’t their job.

Elite Chefs Who Keep the Food in the Kitchen: An expert is brought in to figure out why a restaurant is failing when they have all this top-end chef talent. Evidently customers are waiting forever and often not getting food at all. When the reviewer goes into the kitchen they find stacks of beautiful, perfectly-arranged plates of food sitting next to the stoves. They ask the chef why this food hasn’t gone out to the tables, and the chef answers:

> I know way more about food than these stupid waiters and stupid customers. Do you know how long I’ve been studying to make food like this? Even if I allowed them to eat it they wouldn’t understand it, and they wouldn’t appreciate it. So I keep it here.

Great, so we have waiters to who refuse to take food to tables, and we have chefs who don’t allow their dishes to leave the kitchen. That’s a Red Team that refuses to work with the Blue Team.

If you have this problem, the solution is to fix the Red Team / Blue Team interaction dynamic—not to create a separate group that’s tasked with doing their job for them.

What are Yellow, Orange, and Green Teams?

In addition to the well-known Red, Blue, and Purple team concepts, April Wright > brilliantly introduced a few other team types in a Blackhat talk called, Orange is the New Purple >.

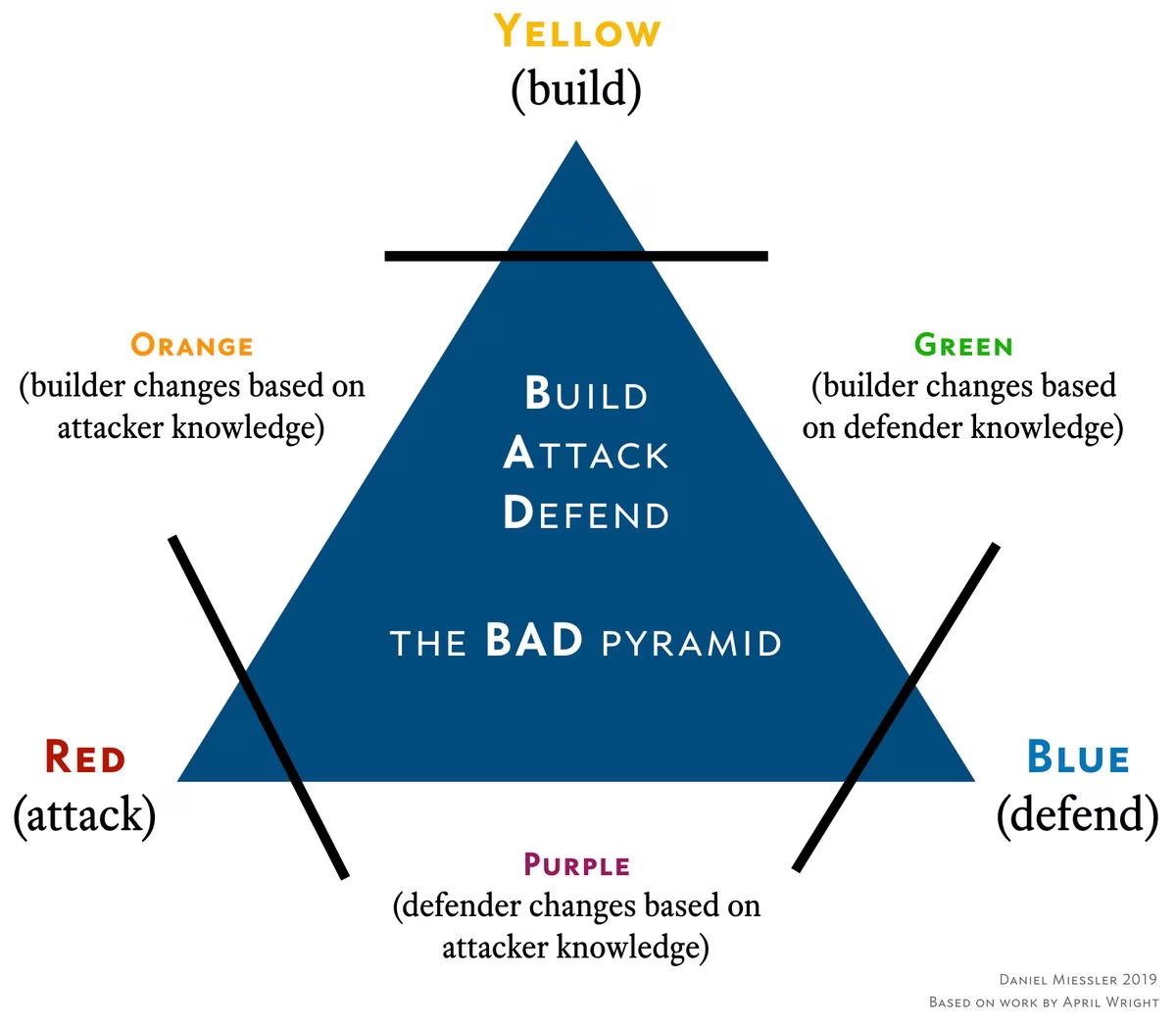

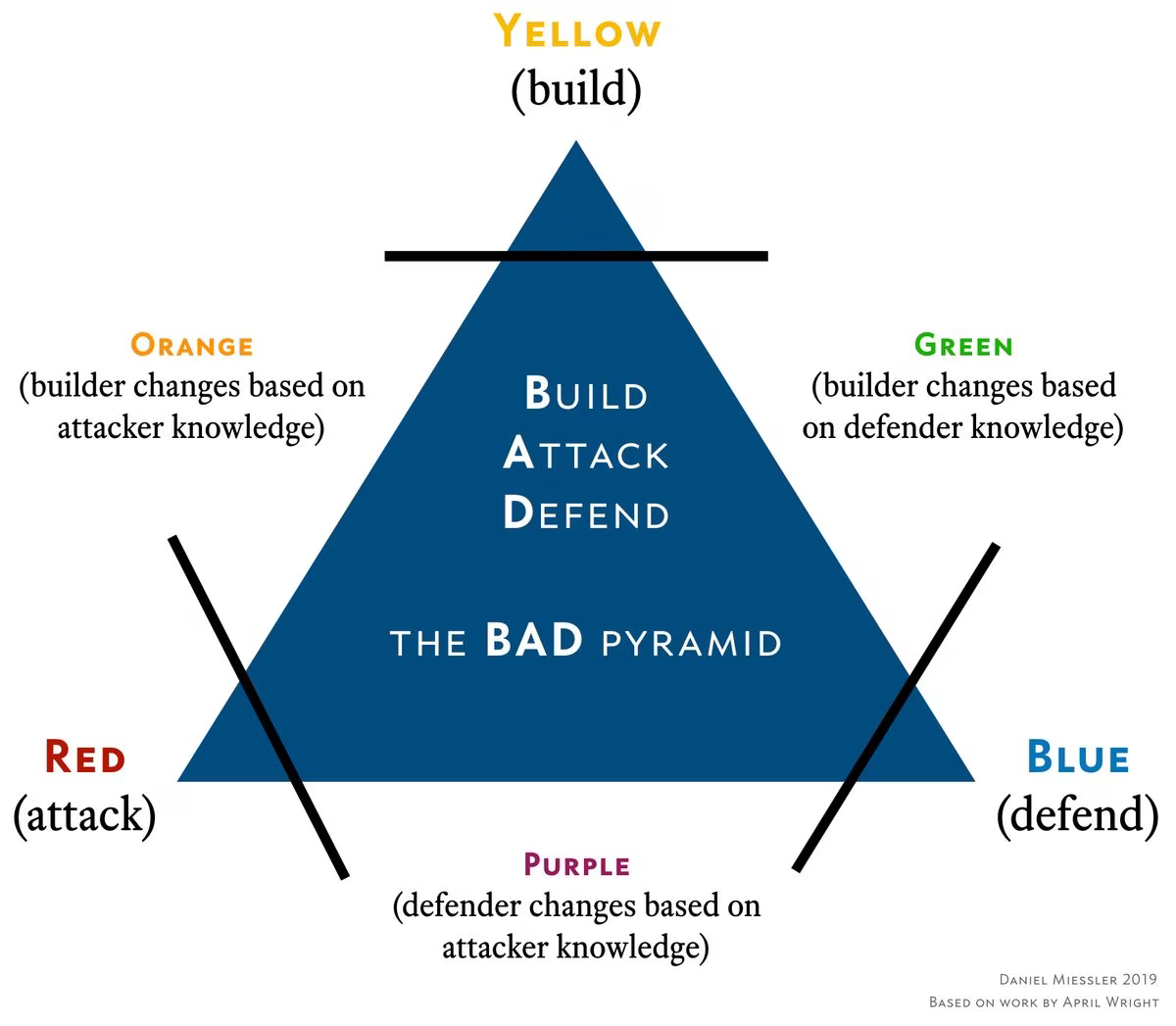

In that talk she introduced the concept of the Yellow team, which are the builders, and then combined them with Blue and Red to produce the other colors. I think this is extremely smart, but disagree somewhat with some of the characterizations of the combinations. I captured my own interpretation of these interactions in what I’m calling the BAD Pyramid above, which is a purely derivative form of April’s work.

I also don’t much care for the word "team" being assigned to all these colors, since I think in most cases they’re actually mindsets, or functions, rather than dedicated groups of people. Yellow, for example, already has a name—they’re called Developers. And the Green, Orange, and Purple designations should really be changes to either Developers or Blue Team behaviors.

A Summary of Security Function Colors

Yellow: Builder

Red: Attacker

Blue: Defender

Green: Builder learns from defender

Purple: Defender learns from attacker

Orange: Builder learns from attacker

Common problems with Red and Blue team interactions

Red and Blue teams ideally work in perfect harmony with each other, as two hands that form the ability to clap.

Like Yin and Yang or Attack and Defense, Red and Blue teams could not be more opposite in their tactics and behaviors, but these differences are precisely what make them part of a healthy and effective whole. Red Teams attack, and Blue Teams defend, but the primary goal is shared between them: improve the security posture of the organization.

Some of the common problems with Red and Blue team cooperation include:

The Red Team thinks itself too elite to share information with the Blue Team

The Red Team is pulled inside the organization and becomes neutered, restricted, and demoralized, ultimately resulting in a catastrophic reduction in their effectiveness

The Red Team and Blue Team are not designed to interact with each other on a continuous basis, as a matter of course, so lessons learned on each side are effectively lost

Information Security management does not see the Red and Blue team as part of the same effort, and there is no shared information, management, or metrics shared between them

Organizations that suffer from one or more of these ailments are most likely to think they need a Purple Team to solve them. But "Purple" should be thought of as a function, or a concept, rather than as a permanent additional team. And that concept is cooperation and mutual benefit toward a common goal.

So perhaps there’s a Purple Team engagement, where a third party analyzes how your Red and Blue teams work with each other and recommends fixes. Or perhaps there’s a Purple Team exercise, where someone monitors both teams in realtime to see how they work. Or maybe there’s a Purple Team meeting, where the two teams bond, share stories, and talk about various attacks and defenses.

The unifying theme is getting the Red and Blue team to agree on their shared goal of organizational improvement and not to introduce yet another entity into the mix.

Think of Purple Team as a marriage counselor. It’s fine to have someone act in that role in order to fix communication, but under no circumstances should you decide that the new, permanent way for the husband and wife to communicate is through a mediator.

Summary

Red Teams emulate attackers in order to find flaws in the defenses of the organizations they’re working for.

Blue Teams defend against attackers and work to constantly improve their organization’s security posture.

A properly functioning Red / Blue Team implementation features regular knowledge sharing between the Red and Blue teams in order to enable continuous improvement of both.

Purple Teams are often used to facilitate this continuous integration between the two groups, which fails to address the core problem of the Red and Blue teams not sharing information.

The Purple Team should be conceptualized as a cooperation function or interaction point, and not as a superate and ideally redundant entity.

In a mature organization the Red Team’s entire purpose is to improve the effectiveness of the Blue Team, so the value provided by the Purple team should be natural part of their interaction as opposed to being forced through an additional entity.

If you combine Yellow (Builders) with Red and Blue you can end up with other functions, such as Green and Orange, that help spread the attacker and defender mindsets to other parts of the organization.

Notes

All these terms can apply to any kind of security operation, but these specific definitions are tuned towards information security.

A Tiger team is similar, but not quite the same as a Red Team. A 1964 paper defined the term as "a team of undomesticated and uninhibited technical specialists, selected for their experience, energy, and imagination, and assigned to track down relentlessly every possible source of failure in a spacecraft subsystem. The term is now used often as a synonym for Red Team, but the general definition is an elite group of people designed to solve a particular technical challenge.

It is important that Red Teams maintain a certain separation from the organizations they are testing, as this is what gives them the proper scope and perspective to continue emulating attackers. Organizations that bring Red Teams inside, as part of their security team, tend to (with few exceptions) slowly erode the authority, scope, and general freedom of the Red Team to operate like an actual attacker. Over time (often just a number of months) Red Teams that were previously elite and effective become constrained, stale, and ultimately impotent.

In addition to being a bridge organization for less mature programs, Purple Teams can also help organizations acclimate their management to the concept of attacker emulation, which can be a frightening concept for many organizations.

Another aspect that leads to the dilution of effectiveness of internal Red Teams is that elite Red Team members seldom transition well to cultures at companies with the means to hire them. In other words, companies that can afford a true Red Team tend to have cultures that are difficult or impossible for elite Red Team members to handle. This often leads to high attrition within internal Red Team members who make the transition to internal.

It is technically possible for an internal Red Team to be effective; it’s just extremely unlikely that they can remain protected and supported at the highest levels over long periods of time. This tends to lead to erosion, frustration, and attrition.

One trap that internal Red Teams regularly fall into is being reduced in power and scope to the point of being ineffective, at which point management brings in consultants who have full support and who come back with a bunch of great findings. Management then looks at the internal team and says, "Wow! They’re amazing! Why can’t you do that?" That’s usually a LinkedIn-generating event.

Other analogies to Red Teams that don’t collaborate: Professional footballers who kick but don’t pass, professional applauders who only use their right hand, professional auditors who don’t write reports, professional teachers who don’t interact with students. You get the idea.

Thanks to Rob Fuller, Dave Kennedy, and Jason Haddix for reading drafts—although I’ve made changes to the article since they’ve endorsed it. (August 2019)

Be sure to check out April Wright’s full BlackHat presentation. More >

Louis Cremen > did a great writeup on April’s work in a post titled Introducing the Infosec Color Wheel >.