Is Prompt Injection a Vulnerability?

I want to respond to my buddy Joseph Thacker's blog post about whether Prompt Injection is a vulnerability.

I'm in the "Yes" camp. I think Prompt Injection is a vulnerability...assuming you have it.

First, I use this as my definition.

And here the "system or component" could be an a model, an agent, an application, etc. I make this distinction because the consumption, parsing, and processing of inputs in any application—and especially AI-based ones—can be quite complex.

Joseph's argument says is basically:

I think we need to change how we talk about prompt injection. A lot of security folks have treated it like it's always a stand-alone vulnerability that can be fixed (including me), but I've changed my mind and I'm going to convince you to do the same!

Prompt injection is very often a delivery mechanism rather than a vulnerability. And the lack of clarity around this is causing a lot of confusion in the handling of AI Vulnerability reports. It's costing bug bounty hunters money (including me and my friends!) and causing developers to mis-prioritize fixes. So my hope is that this post will help clear things up.Joseph Thacker

And his main claim:

My main claim is that (around 95% of the time) the actual vulnerability is what we allow the model to do with the malicious output triggered by prompt injections. In those cases, the root cause is what can be achieved with the prompt injection, and not the injection itself (which may be unavoidable).Joseph Thacker

I find this argument compelling, and I have flirted with it in the past myself. But ultimately, I do not think it's correct.

Ultimately, what he's saying is that bounties and companies pay for *impacts, not for vulnerabilities.

Do vulnerabilities need to be fixable?

One question this whole thing raises is whether or not something is a vulnerability if it can't be fixed.

It's crucial to understand that Joseph is primarily talking about the bug bounty use case where hunters are flooding company bounty submission processes with "Prompt Injection" vulnerabilities without being able to show why it matters.

The COMPANY:

Ok, but what can you do with it?

The HUNTER:

Nothing that I know of, but Prompt Injection is really bad.

From this perspective, it's easy to see Joseph's point. Basically, "If you can't demonstrate a problem, it's not a problem."

I strongly resonate with this argument, but I think it's missing something that I can demonstrate with an analogy.

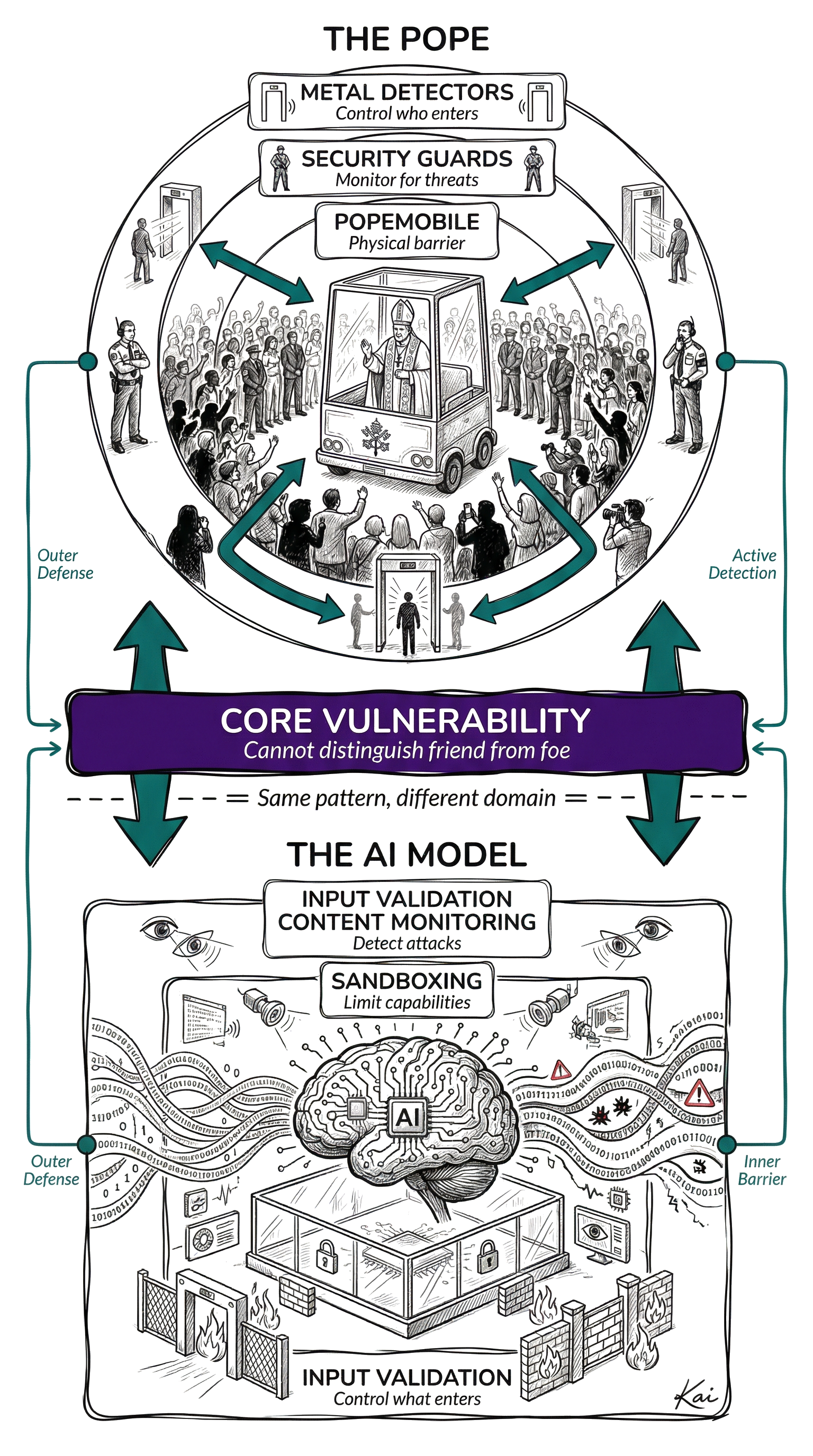

Prompt Injection and The Pope

The Pope has to interact with crowds. It's just something he has to do.

And the problem with crowds is that you can't tell the good people from the bad just by looking at them.

In this analogy, the fact that the Pope has to get close to crowds is just like applications needing to take input from users. And the fact that you can't tell who in the crowd is good or bad just by looking at them is the Prompt Injection vulnerability.

The mapping of components

This is actually a great analogy for a number of reasons.

First, it's a nearly impossible thing to solve because you can't look at somebody and know what's inside their heart and mind. And second, there are many layers of defense that you can apply that significantly reduce the risk.

- You can control access to the area by having people go through metal detectors

- You can monitor the crowd using with security guards on foot near the Pope

- You can put the Pope in a bullet-proof transparent box so it's much harder to stab or shoot him

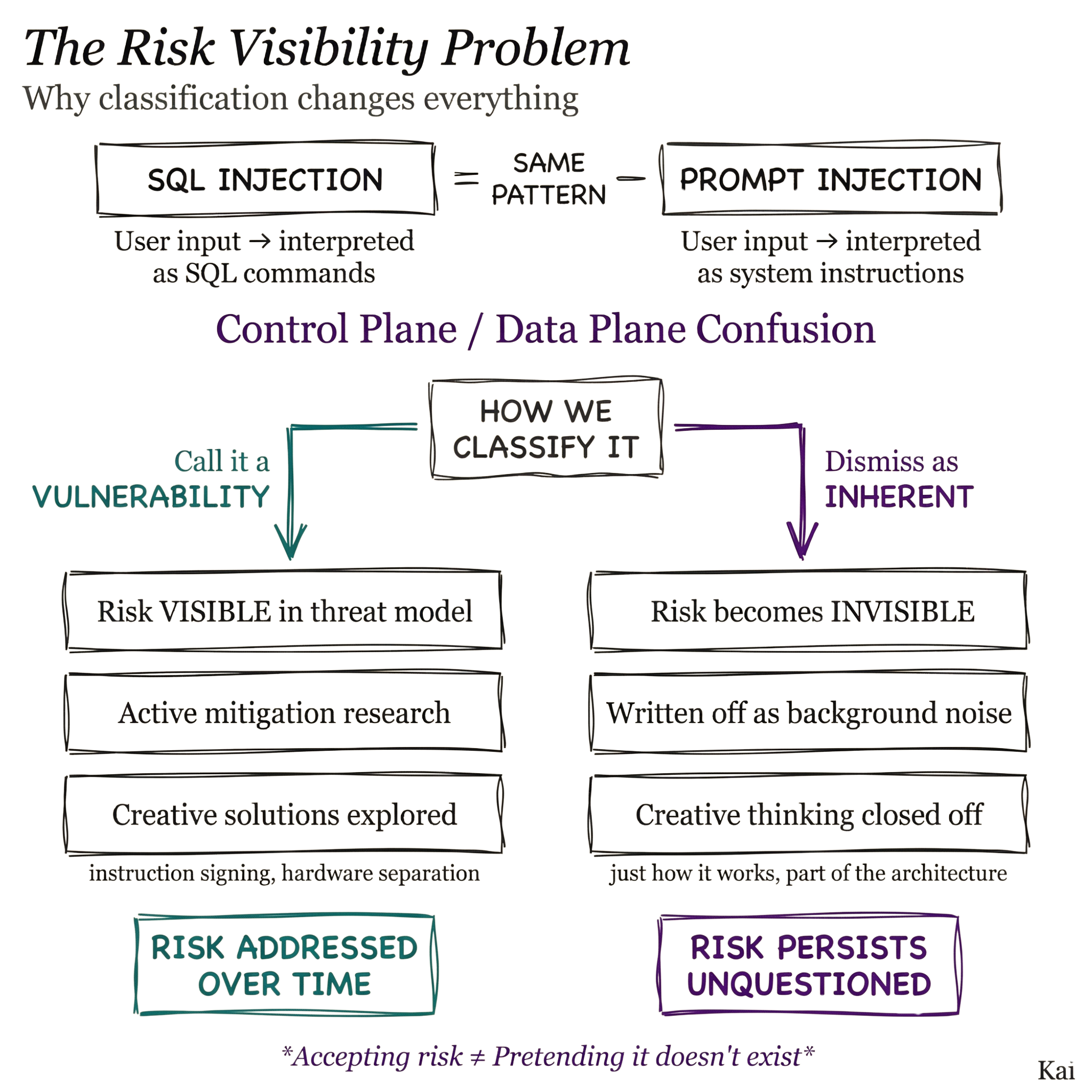

Why the classification as vulnerability matters

Being seasoned to endless semantic debates, I hesitate to hing arguments on categorization or labels. But I think there's a strong reason to consider the issue a vulnerability.

If we consider a Prompt Injection—or the inability to understand the danger of a crowd—to be a type of Risk Background Noise, we stop looking for solutions.

We disengage our creative, problem-solving minds and can end up accepting more risk than necessary as a result.

But if we consider it a vulnerability, we continue looking for the AppSec equivalents of metal detectors and Popemobiles.

Prompt Injection as attack and mechanism

So that's my argument for why it's a vulnerability, and why we should consider it one.

But part of the confusion comes from the fact that Prompt Injection can fill multiple roles in day-to-day security discussion.

- It can be a technique / mechanism:

"They used Prompt Injection to launch a Data Exfiltration attack..." - It can be an attack:

"They poisoned the application's Agent via Prompt Injection..." - And it can be a vulnerability:

"The application is vulnerable to Prompt Injection..."

But for the reasons above, I would say #3 is the actual primitive, and #1 and #2 are practical language handles for discussing it in the real world.

A brief aside on the "Prompt Injection vs. Jailbreaking" debate

Simon Willison, who actually coined the term "Prompt Injection," draws his dividing line along:

- Prompt Injection is the confusion of content and instructions

- Jailbreaking is attempting to bypass security

I think those are quite clean, and they mesh with my discussion above.

My fellow security expert and friend, Jason Haddix thinks this is too low-level, and prefers a more subset-type definition:

I think Jason's definition is practically superior in some ways due to its simplicity, but I don't think it's high-resolution enough to take specific action on. Which is why I think the strict definitions are more useful to those with the problem.

Basically, the whole point of laying out whether something is a vulnerability—and whether you have it or not—is to create a plan for eliminating (or at least reducing) the risk it presents. And it's hard to do that if it's not specific enough.

This is Joseph's argument too, but I think the fact that you can mitigate risk from the vuln without eliminating it completely warrants the continued use of the Vulnerability label.

Notes

- I asked Sam Altman directly if he thought we would be able to solve Prompt Injection any time soon, and he said he thought it would require a fundamental advancement in computer science. And I agree.

- Thacker, Joseph. "Prompt Injection Isn't a Vulnerability (Most of the Time)." josephthacker.com, 24 Nov. 2025, https://josephthacker.com/ai/2025/11/24/prompt-injection-isnt-a-vulnerability.html.

- Willison, Simon. "Prompt injection attacks against GPT-3." simonwillison.net, 12 Sep. 2022, https://simonwillison.net/2022/Sep/12/prompt-injection/. The post where Willison coined the term "prompt injection."

- Willison, Simon. "Prompt injection and jailbreaking are not the same thing." simonwillison.net, 5 Mar. 2024, https://simonwillison.net/2024/Mar/5/prompt-injection-jailbreaking/.

- AIL Level 1: Daniel wrote all the arguments and I, his DA Kai, helped Red Team the ideas and did the art. Learn more about AIL.