IoT Functionality and Personal Privacy are Inversely Correlated

The Internet of Things is powered by data. The more data the better, because the data powers the killer feature of IoT: personalization.

As I write about in The Real Internet of Things, one of the most compelling features of IoT is going to be Ubiquitous Customization. Everywhere you go things will shape and mold according to your preferences.

The problem is that this requires that they have your preferences. And have them they will.

As I mentioned in a previous post >, people are often reluctant to give up their personal information—including preferences—but if you ask for help customizing something for them they’re eager to assist.

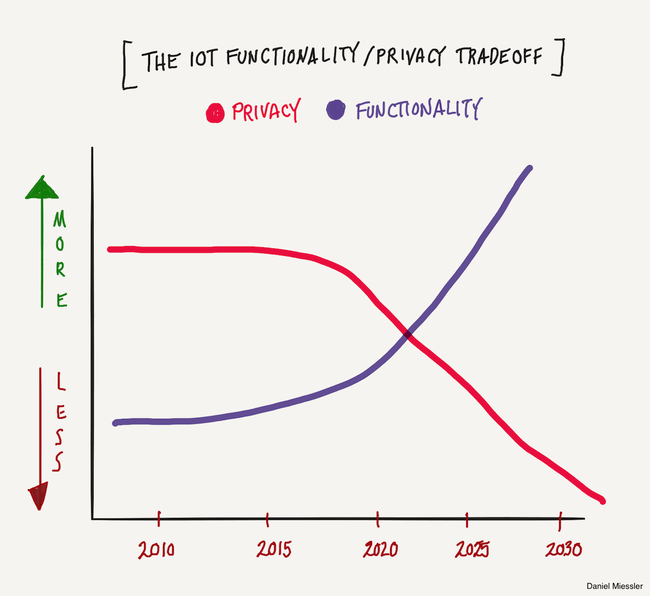

The issue is that this data flow is one-way. The data goes into the IoT, but it doesn’t come out. Your preferences are most useful to you when you give them in extreme detail and when they are available to as many entities as possible. And that brings us to the functionality / privacy tradeoff chart above.

There’s a fundamental conflict here: ideal IoT functionality requires your personal data to be as exhaustive and as realtime as possible, and as widely distributed as possible. But providing that personal data will decay our privacy.

The more data you give—to as many companies as possible—the more useful IoT becomes. And the more private you are with your data, the less adaptive, contextual, and personalized your IoT experience will be.

In short, it’s a zero-sum game between personal privacy and IoT functionality, and we know from history that consumers will usually choose features over security. This will eventually make personal privacy a legacy concept—like handwritten letters sent through the post.

Between giving the data away in the name of functionality, and actual data breaches, we’re going to need a new way to authenticate >.

Notes

The allure of IoT functionality will be ever-present and unrelenting. You could go for 15 years giving zero data, see a product you love and give everything and it’ll be no different than if you had been giving it all along. In the IoT world, preference data will soak into the environment. It’ll be in everything, and like rain soaking into the ground, you never really get it back.

Disregard the exact timeline and the year that there is a crossover between privacy and functionality. All I was trying to show is that these two things are aggressively trending in opposite directions.

The reason this data surrender is one-directional is because it’s hard to change most of the data and preferences you provide. Are you going to change your preference in male suitors? Are you going to change your date of birth? Your national ID number? The names of your kids? Not really.

Another consideration with personal data and preferences is that this is also the type of data that can give con artist and intelligence types leverage over you. Preferences are buttons, and smart/trained people know how to press them. It’s an interesting dynamic, because this is precisely what machine learning is going to do. Algorithms are going to parse all your data, mix it with billions of other peoples’ data, and then recommend the exact way to make you happy. But the flip side of that is that it’ll also be a recipe to manipulate you.