Why I Believe Steven Pinker is Wrong About How Good Things Are (2018)

As I covered in this earlier piece, despite having massive respect for Steven Pinker, and loving his latest book, Englightenment Now, I think he’s very, very wrong about the current state of America.

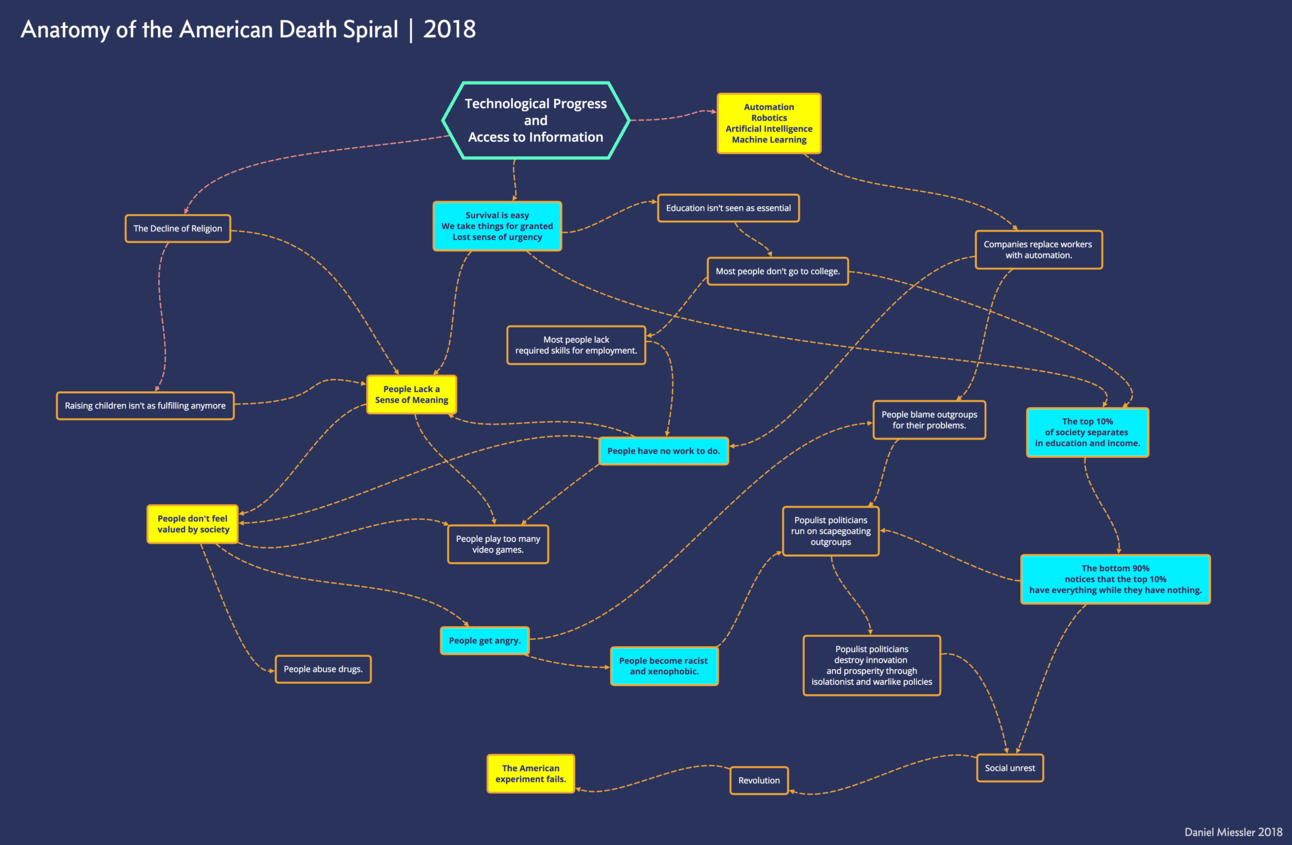

My opinion on this is best described as a feeling of increasing unease—which is an emotion—but I only arrived at that emotion after consuming a great number of reading on topics related to economics, working-class life, and the future of work and automation. The basic argument, broken into individual claims, is captured below.

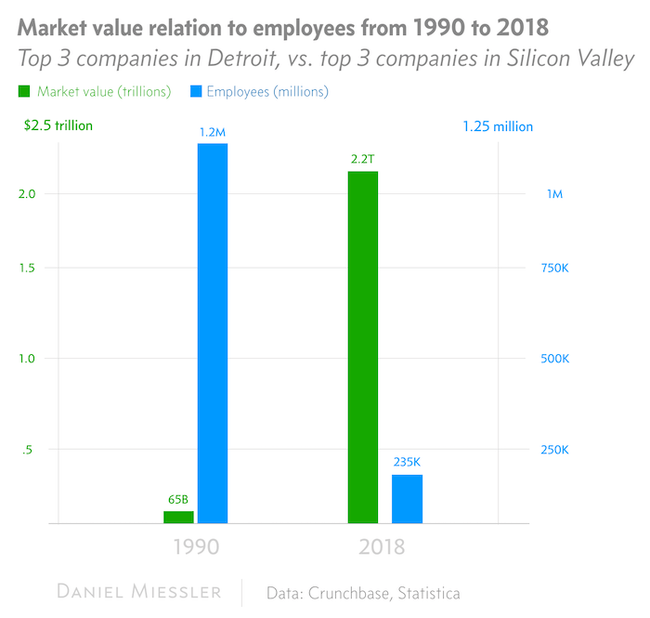

The chart above is my own updated version of similar data presented here by Moshe Y. Vardi in 2016.

- For a number of interconnected reasons, it’s becoming harder for everyday Americans to survive and thrive.

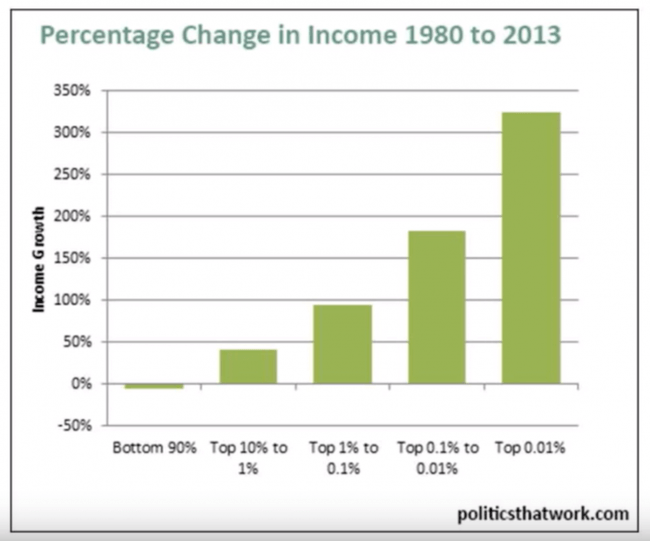

- At the same time, the rich are doing better than any time in recent history, and income inequality is quickly moving towards recent historical maximums.

- A big part of this is the fact that technology is becoming better at replacing human workers, and AI and robotics are about to remove millions more jobs.

- AI is a threat to human work unlike anything we’ve seen before because it has the ability to permanently render humans as inferior to machines for most types of work.

- Some of those jobs will be replaced by new types of work that humans will be better at (for now), but they will often require a skill or talent level that most of the displaced and new workers won’t have.

- Human meaning is deeply tied to feeling valuable, and having millions of people who are unable to do anything that a machine can’t do better, is going to be a humanity-scale challenge.

- With the great depression and the recent recession, it was accepted that there were fewer jobs right now, but that they’d eventually come back. That’s the part that’s different: because of AI and automation, millions of those jobs are going away permanently.

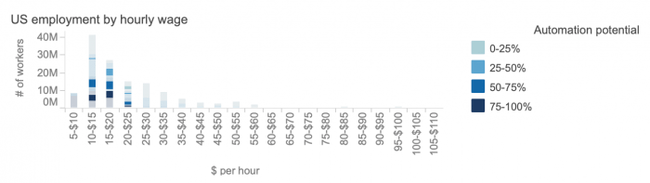

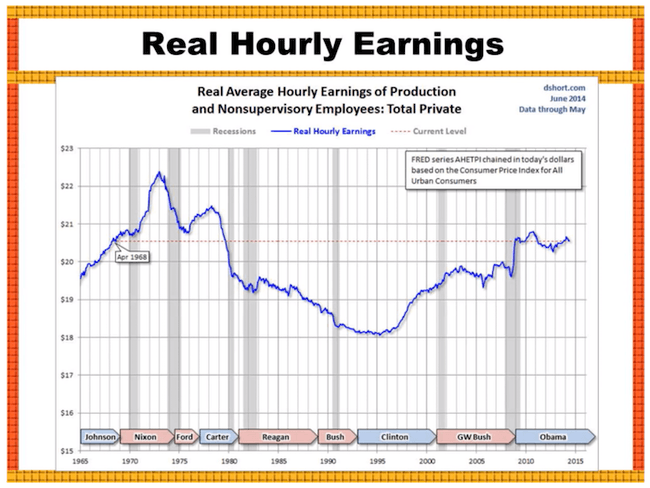

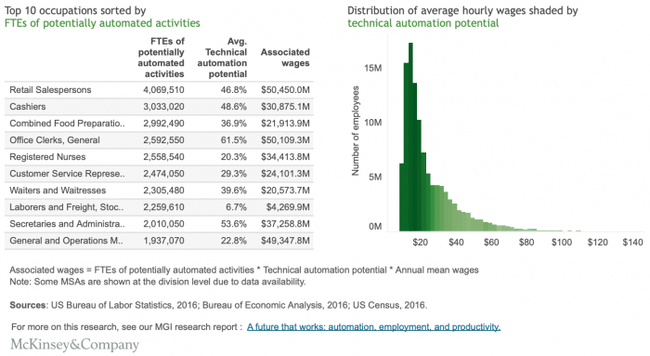

The hourly wage chart shows what I believe to be the core of the problem, i.e., that the people who will be most affected by automation are already the lowest paid, which will lead to even more social tension in coming years.

- Many companies—especially large ones—see their human workforce as a major detriment to productivity and profitability, and are actively seeking ways to improve their bottom line by replacing them with technology.

- Companies are also transitioning their workforces to temporary workers in various different ways because they impart less of a financial burden on the business and give them more flexibility to expand and contract their workforce—ultimately reducing costs.

- These changes from permanent-hire to part-time employee, contractors, or gig economy workers are often associated with highly undesirable working conditions for those workers, including reduced hours per worker, unpredictable work schedules, a lack of benefits, and the constant threat of having work reduced.

- Having millions of people who don’t feel useful or appreciated at work is bad. It will make people depressed. It will make people angry. And they will point that anger at others.

- This anger will open the door to populist leaders who will use it to foster nationalism, scapegoating, xenophobia, and other negativity observed in turbulent times in the past.

- Opportunistic politicians will not solve the problem, however, because the underlying issue is the impending obsolescence of human labor. That is the thing we must address.

- For all these reasons, we need to first acknowledge how bad the situation has the potential to become—up to and including a breakdown of society and/or social upheaval and revolution, and second—start taking serious, practical action to find new ways for humans to feel like valuable contributors to their loved ones, and to society.

This is my own working mindmap on the various causes, effects, and correlations at play.

That’s the overall flow of the argument, and I feel I’ve arrived at this position through careful consideration of what data exists today. But this is seldom enough—even for me.

Many (and one friend in particular) believes that the AI and automation threat is just like previous threats to human work that we saw in the industrial revolution, the depression, and in the recession of 2008. He thinks we’ll bounce back, as humans, like we always do.

I used to agree with him, but now I think he’s wrong. It’s different this time, and here are some of my favorite reading that brought me to this conclusion:

- Humans Need Not Apply, Jerry Kaplan

- Life 3.0, Max Tegmark

- What Do You Think About Machines That Think, John Brockman

- The War on Normal People, Andrew Yang

- Homo Deus, Yuval Harari

- Prediction Machines, Ajay Agrawal

- Bullshit Jobs, David Graeber

- The Evolution of Everything, Matt Ridley

- Algorithms to Live By, Brian Christian

- Superforecasting, Phillip Tetlock

- Player Piano, Kurt Vonnegut

- Sleeping Giant, Tamara Draut

- Capital in the 21st Century, Thomas Piketty

- The Master Algorithm, Pedro Domingos

- The Inevitable, Kevin Kelly

I’m sure I missed a few, but those were the main ones—combined with hundreds of articles of course.

But the reason for this post is not to try to convince you again through crisp or alarmist prose, or by telling you to go read all those reading (although I do recommend you do that). The issue is that I need to be able to make data-backed arguments on the fly. As it turns out, it’s pretty hard to recall hundreds of data points from dozens of reading you’ve read on a topic over five years.

So I created this post to avoid feeling like I was peddling religion instead of presenting a data-based opinion—to whatever degree possible given our epistemic limitations. As such, this is going to be a running collection of data points, references, sources, links, etc., that support the position above. I hope you find it informative.

Jobs, finances, and mental health

- Real hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers (most of the workforce) is the same as 1968, which combined with inflation is why people are finding it hard to stay above water. Link

- The share of the economy coming from work (as opposed to wealth) is dropping very quickly. Link

- 59% of American workers are paid hourly as opposed to being salaried. Link

- 66% of jobs in the US pay less than $20 an hour. Link

- U.S. renters make an average of $16.38 an hour, but to afford rent in a 2-bedroom home you need to make an average of $21.21. Link

- The only income improvements since 1980 have come to the top 10% of income earners, and the bottom 90% actually lost ground. Link

- 43% of U.S. households can’t afford monthly bills such as rent, food, child care, healthcare, and a mobile phone. Linkand why it matters.

- 40% of Americans couldn’t cover a $400 emergency expense without selling something or borrowing money. Link

- Only 15% of Americans have more than $10,000 in savings, and almost 70% have less than $1,000. Link

- The mean credit card debt in the U.S. is $5,700 per household, but for households that are carrying debt it’s $9,333. Link

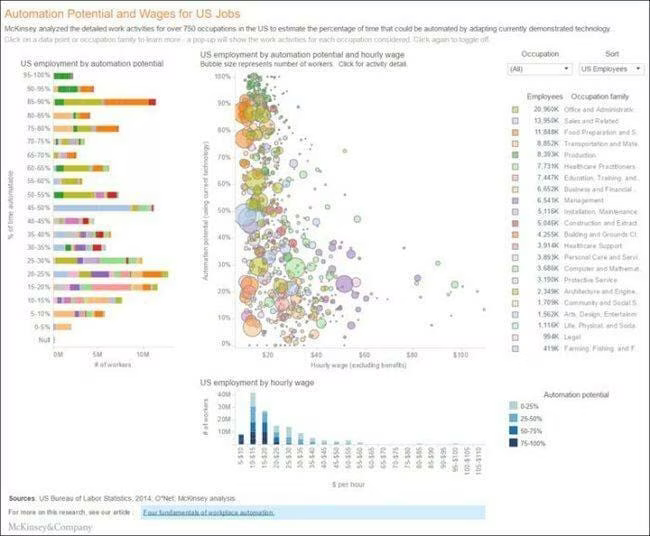

AI, automation, and jobs

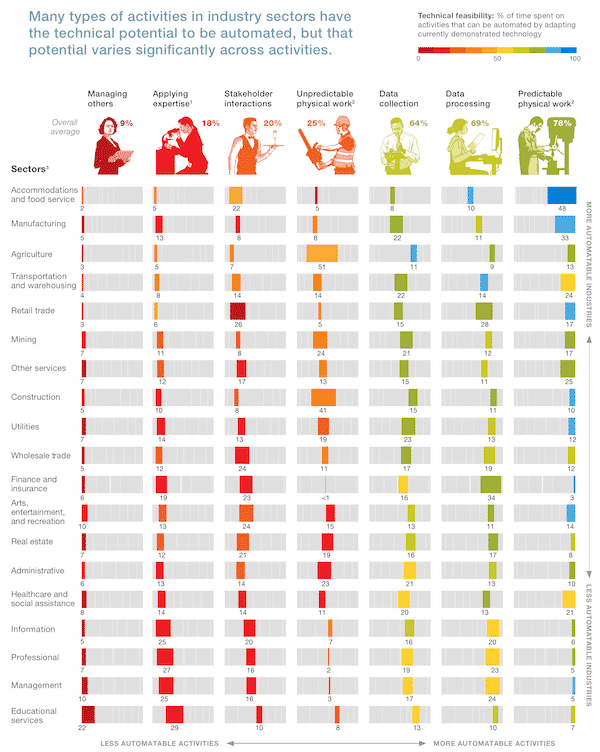

The Technical Potential for Automation in the US

- Support for unions is now at a 15-year high, at 62%. Link

Some of the study authors think there will be easy transitions to other jobs for many of these workers, but I think that’s less grounded than the loss predictions themselves.

- McKinsey says automation could remove up to 73 million US jobs by 2030. Link

- 83% of jobs where people make less than $20 per hour will be subject to automation or replacement according to at 2016 White House report. Link

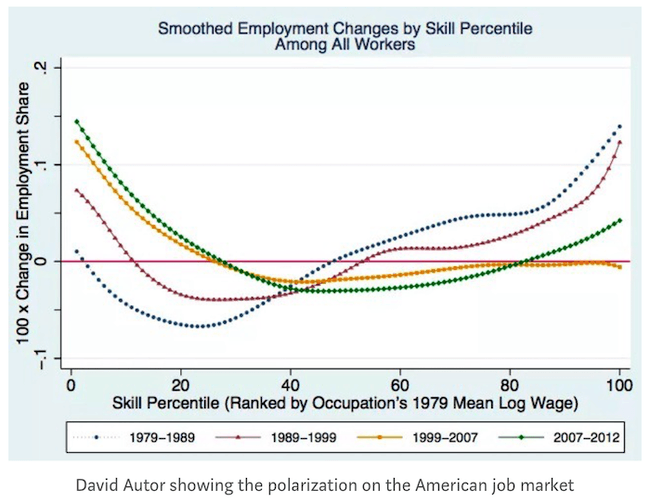

- The people with jobs are going to be those at the very top (creativity and broad skillsets) and the very bottom (manual and too expensive to automate), which will further separate the classes and cause social strife. Link

High-wage workers are expected to be less affected by the sweeping changes because they have skills that machines can’t replace. Low-wage jobs also could grow rapidly, partly because they cost employers less and so are often not worth supplanting with technology, while many are in health care, such as home health aides. That means middle-wage jobs will continue to decline, widening the divide between wealthy and low-income households, the report says.USA Today

- Between 64 and 69 percent of data collecting and processing tasks common in administrative settings are automatable: McKinsey Global Institute, A Future That Works: Automation, Employment, and Productivity, January 2017 Link

- McKinsey says around 50% of current work activities are automatable by currently demonstrable technologies, with 6 out of 10 current occupations having more than 30% of activities that are automatable. Link

- Goldman Sachs useded to have 600 taders, and now they have 2. They hired 200 software engineers to replace them, which—of course—isn’t a permanent position. Link

Summary

I’ll continue updating this post’s data section as new studies and estimates come in, but hopefully this short collection of data and analysis will give pause to anyone who thinks we’ve been through this before.

Notes

Notes

- There is a must-read / watch book and video called Humans Need Not Apply MORE

- Jan 27, 2021 — I just updated the mindmap image because it was too small and blurry to read, but I’ve not changed a single letter of text since this was originally published in 2018. This, unfortunately, turned out exactly as Andrew Yang and I predicted.

- February 6, 2024 — Well, it appears this piece continues to get more and more real as time goes on.