An Evolutionary Explanation for Our Experience of Free Will

by Victor Zanetsov

July 10, 2013

It’s pretty easy to argue that we don’t have free will, but it’s as least as easy to see that we do in fact experience having it. One argument I often hear about how free will cannot be an illusion is that evolution obviously selected for it, and that nobody has given a good explanation for why.

Let me help frame what I believe their argument to be:

If free will is an illusion, then why did evolution select for us experiencing it? Or, to put it differently, if evolution didn’t select for the advantage of free will (the real thing), then what advantage did the EXPERIENCE of having it offer that merited it being selected apart from actually having it?

It’s a great question.

First, I bet it’s untrue that no one has given a good explanation for why evolution could have selected for the sensation/illusion/experience of free will; I think it’s much more likely that these commenters simply haven’t read those explanations. In their defense, though, I have read a decent amount on this topic and haven’t seen a good explanation either.

So here’s my theory, and keep in mind that I break into computers for a living; I know crap about biology above high school classes and the five reading or so I’ve read on evolution from Dawkins.

Usefulness abstracted from truth

To me the illusion of authorship of our actions simply seems immensely useful. And usefulness is what gets traits and behaviors selected.

One thing consciousness does for us is allow us to contemplate our actions, past and potential, and to think about their outcomes. From there we can evaluate which outcomes we want, and take action accordingly. This is powerful, and it clearly offers an advantage over other animals that cannot perform such analysis.

But what about the feeling that we are performing these actions? Why would we evolve that? Why not just keep that analysis ability but not get the sensation of authorship?

I think the answer is that it offered a massive advantage in our ability to build complex societies. As soon as you begin dealing with groups of people, in a survival scenario (as every scenario was back then), it seems like the notion of "attribution of action" suddenly becomes key.

Where you have attribution you have blame and praise, and where you have blame and praise you have an innate incentive to take actions that will produce the best outcomes for yourself, your family, and your group.

More pointedly, blame and praise serves as the foundation for fairness and criminal justice. Once we can blame people for their actions we can start discouraging behaviors that are deleterious to the community, and removing negative actors in this way gives that society–and the people in it–a significant advantage against groups who cannot do so.

And remember, the issue of "not really true" doesn’t matter to evolution. Evolution is epistemologically encapsulated in a way that we are not. We are free to contemplate things we cannot be sure of, while natural selection lives firmly in the world of the practical.

Stated differently, evolution deals with the advantages of Practical Free Will >, while the illusory nature of free will refers to Absolute Free Will >.

I think this explanation serves dutifully in explaining the usefulness of Practical Free Will, i.e. the experience we have of authoring our actions.

Notes

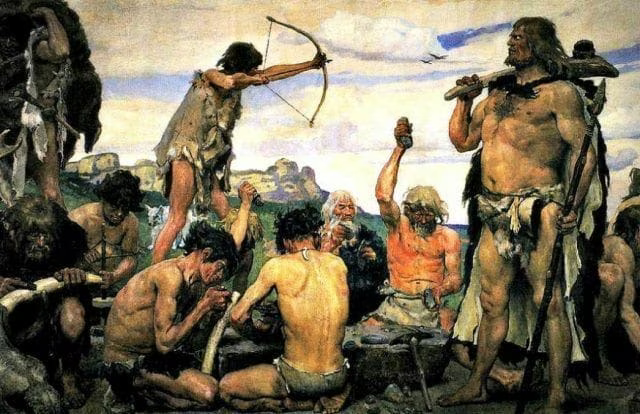

Image from ananael.blogspot.com.